The Old Secrets of Shindō Musō Ryū

The koryū martial arts of Japan–arts that were established prior to the Meiji Restoration of 1868– seem to be surrounded with mystery, magic, fable, and secrets. Origin stories often involve days or weeks or months or even years of sacrifice and self-disclipline by a founder, with visits to caves, long sojourn’s in the mountains or forests, time practicing on holy ground. These efforts were often rewarded with inspiring visits by gods, goddesses (or their messengers) or the occasional mountain tengu. My art, Shindō Muō ryū, has such a founding story, and holds its share of mysteries, spiritual practices, and secrets. In this essay, I want to return to the theme of secrets taken up in Part One, but this time we focus on old secrets.

By “old secrets”, I mean things that were considered secrets from the origins of the art (around 1610), or at least as far back as our earliest documents (1720). You can think of these as secrets that are “baked in” to Shindō Musō ryū. These are different in kind and nature from the modern secrets I wrote about in Part 1. When it comes to the old secrets, it is public knowledge that the most important secrets exist. The critical old secrets are the 5 secret kata organized into a set called, variously, the Go Musō no Jō, the Hiden Gokui, or just the Gokui. Books on Shindō Musō ryū typically acknowledge the names of the kata in the set as we know it today, and the set is included in most koryū group’s list of kata that they practice (if they publish their curriculum). Knowing they exist is a world away from knowing the kata themselves. For most members of the ryū, these kata are the known unknowns of Shindō Musō ryū.

There is a second kind of secret that I want to touch upon as well: the oral teaching that accompanies the Gokui kata. The existence of such a secret or secrets may be unknown even to some kaiden. Before I explore the oral teaching, we need to examine a few Menkyo scrolls, look at the evolution of the Gokui kata, and the contents surrounding the presentation of those kata. Going through the scrolls shows how we went from three secret kata to five kata and also how we developed the distinctive imagery and arrangement of the Gokui in our written records. Pushing beyond the written records, I want to offer a theory of what happened to our secret oral teaching and then share what I know about its content–at least in broad strokes.

A Vision in a Cave: Musō’s Shintaku and the Gokui

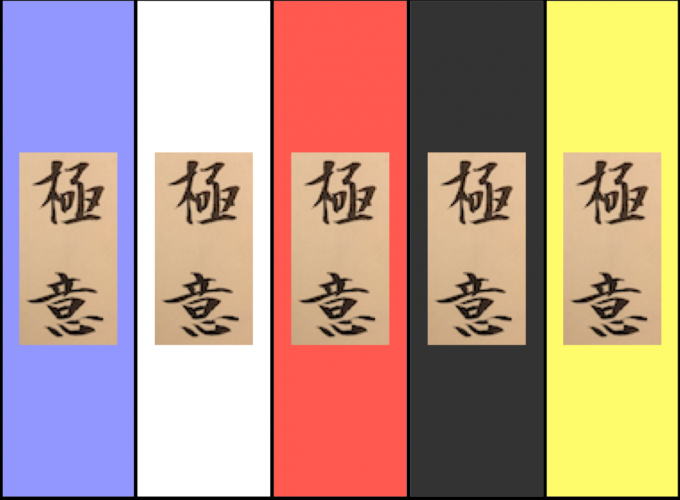

“Gokui” is what is written on modern Shindō Musō ryū menkyo scrolls before the names of the five secret kata: Yamiuchi, Yumemakura, Murakumo, Inazuma, and Dōbo. The word, “gokui,” literally means “secret” and in this context implies the mysteries or secret principles of the art. The Gokui kata set is supposed to be reserved for the menkyo–the masters of Shindō Musō ryū. One explanation I have heard is that if you have even one of the Gokui you can be considered at menkyo level, but there may be disagreement on this score. However, if you come from a credible line of the ryu, have received all 5 kata, can perform them and pass them on, then I think that all Shindō Musō ryū lines would agree that you should be considered kaiden.

inking of “gokui from author’s collection on five banners. My advice is to learn to read “gokui” now to make the makimono images below a little easier to follow.

The first thing that most members of the ryū would say about the Gokui, after telling you there are five kata, is that these secret kata were left us by the founder, Hirano Gonbei, a.k.a. Musō Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi. If asked the formal name of the set, many members of the ryu would probably say it is called the Go (5) Musō no Jō. These kata are said to contain the essence of the ryū as inspired by Musō’s time in Fuchi Cave.

The story is that Musō spent 37 days in a cave on sacred Mt. Hōman, near Daizafu, emerging after a dream in which a young boy brought him a message–a shintaku (神託) or divine revelation. His shintaku translated to English means “take a round stick; know the suigetsu.” The fact that this shintaku is not a secret is surprising, since it is something heaven sent, and marks the summary of Musō’s vision earned after (probably) years of preparation and then weeks of hard spiritual work in a cave on a holy mountain. In any case, after receiving his shintaku he probably worked alone on the mountain, settling on a size for his jo and developing applications that came to be recorded in the Gokui kata. Sometime later he started the process of creating kata that could be taught to students, and those form the core of the art that has been passed down to us.

Of course Musō’s shintaku is ridiculously ambiguous in some ways. It tells us what weapon we should adopt (although there is a range of meaning in what constitutes a proper choice of “stick”), but the admonition to know the suigetsu is so dense with meaning, real and potential, that you can tell this to anyone without giving away anything of value. “Suigetsu” is a kind of Rorschach test word that evokes from the recipient whatever it is they think the word should mean in context. So this is perhaps an open secret camouflaged by ambiguity and hides securely behind the cloak of appearing not to be a secret at all. Anyone can get access to the slogan, but no one should be overly confident they understand its meaning (nor assume there is only one meaning).

Musō receiving a dream vision from the messenger of a god in a holy cave on a divine mountain is a great story. The problem is we have no written evidence that there were five gokui kata left us by Musō, or (being honest) that he left us any kata at all, or (being brutally honest) that there really was a Musō! I am unaware of any verified documentation of his kata from his hand (if anyone can produce such a document, I would sincerely appreciate being corrected–I really want to be proven wrong in this claim!). The earliest “menkyo” scroll I have seen is from more than 100 years after Musō is thought to have exited the cave.

By the way, if a careful tracking of changing kanji in old scrolls is not your thing, you can skip the next section and jump to the “Highlights of the Gokui’s Evolution” below to get a short version and then move on through the essay. Me? I am a glutton for old documents so I turn now to the evolution of the way the Gokui were represented over time in the denshō.

Five Secret Kata?

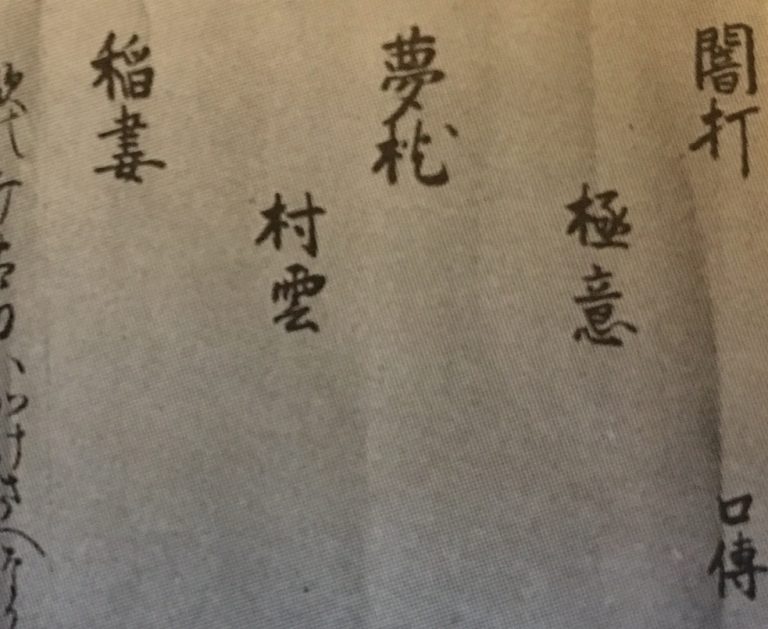

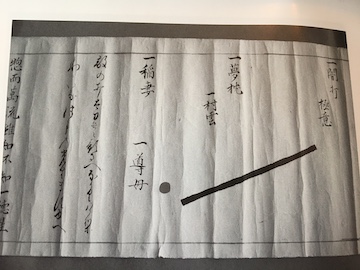

Well, then we know we had five gokui kata by the time of that 1720 scroll, right? Nope. That scroll, from the fourth headmaster Higuchi Hanzaemon to fifth generation instructor Yokota Hanzaburo (who is not in my direct lineage), was issued in 1720. That scroll lists just three kata designated as “Gokui”. A fourth kata, Yamiuchi (meaning “a strike in the dark”), is listed before the “Gokui” designation. Today we consider Yamiuchi to be the first of the Gokui, but it appears that in 1720 it stood apart, outside the Gokui “set.”

reproduced from an image of Higuchi’s 1720 scroll included in Hiden Koryū Bujutsu, v. 6, 1991

What makes Yamiuchi significant in this scroll is not only that it stands outside of the Gokui set, but there is a notation directly beneath Yamiuchi that simply reads “oral teaching”. That implies there is a secret associated with Yamiuchi SO SECRET that you can only mention that there is a special teaching that cannot even be written down. So while Yamiuchi is apparently not counted as one of the Gokui, it does stand out as having its own “gokui”–secret–attached to it. By the way, Matsui Kenji Sensei speculated that the indentation of the second kata named after the “Gokui” entry, Murakumo, indicates that it was not an original kata from Musō, but a product of a later teacher. Of course it is impossible to know, but that seems a reasonable interpretation.

By counting Yamiuchi as one of the Gokui the best case is that we received four kata from Musō (worst case–only three kata come down to us from the founder depending on how you view Murakumo) that were counted as having a secret or being a secret as of 1720. Where is the fifth kata to fill out the Go Musō no Jō?

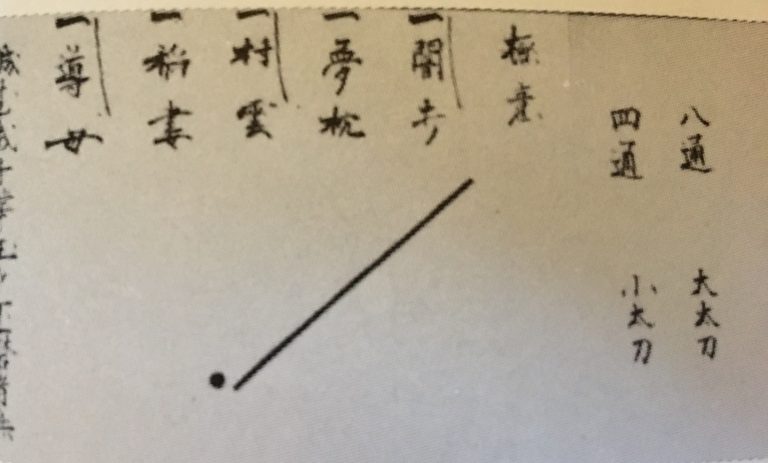

The next oldest menkyo scroll I have access to and most people will find (it is reproduced in the after-piece of Kaminoda’s Jōdō Kyohan, 1976 so many readers of this article can get access to it for their own inspection) was issued in 1768 by Nagatomi Kotarō of the seventh generation. Nagatomi Kotarō’s notation on the secret kata starts “Gokui” followed by the kata Yamiuchi–so now that kata is clearly classified as part of the secret set. A new kata name has been added at the end, it is read Dōbo. The five kata listed here are written with the same kanji that are used in today’s menkyo scrolls (it is impossible to know if the physical content of those kata is unchanged). In less than fifty years we went from 3 or 4 secret kata to 5 secret kata.

Where did Dōbo come from? Who created it? Matsui Sensei found that 5th generation instructor, Harada Heizō, included Dōbo in his menkyo scrolls. I do not have an image to share of those materials. Harada was of the fifth generation, and established a new line of Shindō Musō ryū (written with characters for New Just) distinct from Yokota’s “True Path” line; it is Harada’s line that produced Nagatomi Kotarō and comes down to all modern members of the ryū. Barring discovery of other materials that show an earlier origin, it would appear that it was Harada who was responsible for creating this fifth Gokui kata. (Matsui S. wrote two articles that appeared in the magazine Hiden Koryu Bujutsu in 1991, volumes 6 and 7; these were translated into English by Hunter Armstrong, edited by David Hall, and then published in English as “The History of Shindo Muso Ryu Jojutsu” by the International Hoplology Society in 1993. My reference to Matsui’s claims comes from Armstrong’s translation or from the original images included in Matsui’s article.).

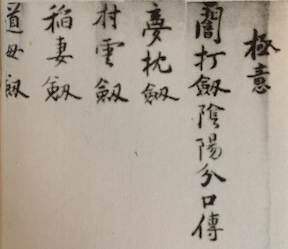

Nagatomi Kotarō gokui section from 1768 scroll, from Jōdō Kyohan

Pay special attention to the new kanji found directly under Yamiuchi in Nagatomi Kotaro’s Gokui. Instead of the vague, “oral instruction” of 1720, it appears to read 陰陽分口傳 (in yo bun ko den), which might be translated as “oral teaching to transmit knowledge from yin and yang theory.” Whether this signifies something very specifically from formal Onmyōdō practices (this school developed in Japan from Taoist influences beginning in the 7th century and was primarily associated with divination for the Imperial Court, but had been in decline even before the Tokugawa came to power so it seems unlikely that is the reference here) or something more generic about yin and yang is uncertain. Either way, by the 1760s one of our menkyo scrolls indicates that we have an oral teaching about Taoist, or yin and yang, philosophy associated with learning the kata Yamiuchi.

It appears that Shindō Musō ryū’s secret kata evolved in the 18th century. Our ryū gained one or maybe two secret kata, depending on the somewhat vague status of Yamiuchi circa 1720. We also find two different kinds of notations alerting us that there was an oral teaching associated with Yamiuchi. We keep our secrets in Shindō Musō ryū, but occasionally we change them too, or at least how we write them down. We do not know if the special teaching referred to in 1768 is the same in content as the vague allusion to “oral teaching” from 1720 or whether it had changed in the generations between Higuchi and Nagatomi. Note that the evolution of gokui kata from 3 or 4 to 5 implies that the widely used name of this set–Go Musō no Jō–is no older than the 5th generation of headmasters as there were not 5 kata until after 1720. Finally, it is striking that Nagatomi Kotarō did not indent any of the kata but simply lists them in a single, level line.

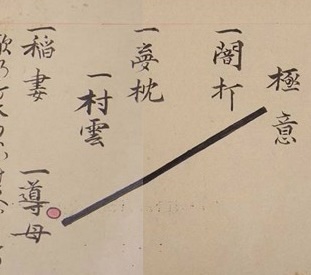

Looking at the documents of another line, the Minagi Kuroda line responsible for providing civil order for Chikuzen province outside of the Kuroda daimyo’s capital, we see a change in presentation. First, a 1781 (Anei 10) menkyo scroll by Inoue (7th generation like Nagatomi Kotarō), makes no mention of an oral teaching, but has adopted a mostly modern arrangement around the gokui.

from “The Tradition of Shindō Musō ryū of the Minagi Kuroda of Chikuzen Province” privately published by Daizafu Jōdōkai Research Material Compilation Committee, 2010 (translation by author); the photo above is from an 1843 Minagi-line scroll, but it is the same as that described as having been issued by Inoue in 1781. Inoue’s scroll is reproduced in modern type-setting on pages 46-47.

Inoue still lists the kata Yamiuchi before the label of Gokui. He makes no special notation about oral teachings associated with Yamiuchi. However, according to the Daizafu Jōdōkai’s publication, Inoue includes a drawing of a jo as well as a small red circle. These are familiar to modern eyes as this drawing and circle have been included in all the modern scrolls I am aware of. My understanding is that the circle being colored in signifies complete transmission and receipt of kaiden; Inoue uses red ink for this “dot”. (An unfilled circle signifies just holding the menkyo.) In contrast to Nagatomi Kotaro, Inoue has the indentation of Murakumo that we associate with the Higuchi scroll of 1720, and then Dōbo is also indented as well. The organization of this section is strikingly “modern” in that it looks almost identical to those by Shiraishi and his 20th century line (which covers all the surviving menkyo kaiden of Shindō Musō ryū) except we always list Yamiuchi as the first Gokui kata.

Moving into the early 19th century, ninth generation kaiden, Nagatomi Jinzo, of the Haruyoshi branch of New Just jōjutsu in Fukuoka, issues a Menkyo scroll around 1816 which looks quite similar to that of Inoue. He has the jo, the circle and lacks any mention of oral teachings. However, he followed Nagatomi Kotaro’s practice by placing the word “gokui” before the kata Yamiuchi. Further, he abandoned any effort to list the kata with different levels of indentation, instead adding a simple vertical line before the three kata that it is thought were “added” to the Gokui: Yamiuchi (which I believe comes from Musō, but was not originally assigned to the category of “Gokui”), Murakumo, and Dōbo–at least I assume that is the significance of these lines.

Nagatomi Jinzo gokui section circa 1816. image from Jōdō Kyohan afterpiece

Did Inoue of the Minagi line not have the secrets? Is that why he drops references to oral teachings? Is it possible that Nagatomi Kotaro neglected to pass to his successors the secret teachings that should have come down from his line? Were they lost, or had they become so secret any mention of them would be viewed as problematic? We cannot know the answer to these questions, but I have reason (that I will address below) to believe the oral teaching survived.

For completeness regarding written representation of the Gokui set, I am including a photo of a menkyo makimono issued by Shiraishi Sensei in 1927. It shows that the representation of the Gokui looks like Inoue’s, but lists the kata in an order consistent with that of Nagatomi Kotaro’s scroll. I believe that Shiraishi’s menkyo scroll became the model used in modern Shindō Musō ryů.

Shiraishi gokui section. image captured from a Yahoo.jp auction.

Highlights of the Hiden Gokui’s Evolution

To summarize the changes in what and how the Gokui are recorded:

- 1720 Higuchi (4th generation) issues Menkyo scroll with Yamiuchi not included as part of the Gokui and there is no Dōbo kata so there are only 3 Gokui kata; Yamiuchi has an “oral teaching” ;

- By 1734, Harada Heizō (5th generation), a student of Higuchi, issues a scroll that includes Dōbo (this scroll is not reproduced here, but I am reporting Matsui Sensei’s finding) bringing the Gokui to four (we know this happened before 1734 because Harada is variously reported as having died in 1733 or 1727) with (I infer from the context of Matsui’s writing) Yamiuchi still not listed as a Gokui kata;

- 1768 Nagatomi Kotaro (7th generation) includes Yamiuchi as a Gokui kata and adds a notation “a branch of yin yang knowledge” under Yamiuchi–now there are 5 kata in the Gokui in the line of jōjutsu that comes down to modern practitioners;

- 1781 Inoue (7th generation) includes a staff and dot image and organizes the kata in a “modern” style; no mention of special teaching for Yamiuchi (which he keeps as separate from the Gokui) and Inoue’s (now expired) line continues to leave Yamiuchi outside the Gokui set.

- 1816, Nagatomi Jinzo (9th generation) has five Gokui, but no mention of any secret oral teaching is recorded in the makimono.

There are missing pieces here as I do not have access to all the known records nor did all the denshō of the ryū survive. Was Inoue the first to use a jo and dot image in his scrolls? Probably not, just the first I have an image of. Was Inoue the first to not mention a secret teaching associated with Yamiuchi? Perhaps. So there is bias in the treatment of questions around the Gokui based on what records I have seen or that Matsui Sensei reported on in his 1991 articles. However, I think this illustrates pretty well rough chronological evolution of what we count as Gokui kata, and how we came to lay out the Gokui section in our modern scrolls the way that we do (and I assume the Fukuoka line is similar to the Tokyo line since we both come down from Shiraishi).

The result? We can say with confidence that not all 5 secret kata come from Musō Gonnosuke. We can say with confidence that by the mid-18th century at least one line of jo (and this is the line that comes down to modern practitioners) had reorganized the Gokui to get us to five secret kata by counting Yamiuchi as the first of the Gokui and through the creation of Dōbo (probably by Harada). We can say with some confidence that by the early 19th century, menkyo kaiden that stand in the modern line of jōjutsu were not writing notations under Yamiuchi posting notice of oral teachings regarding yin and yang. Those notations about secrets were left out of official denshō.

Hiding Secrets? The Turn Against Secrecy and Foreign Influence

Why were written references to a secret oral teaching dropped from our records? There is no way to authoritatively know, but I am going to propose a speculative explanation for the erasure of written references to secret oral teachings. A double movement in political and bureaucratic values marked the Tokugawa jidai and may account for the disappearance of these explicit references to secrets.

First, the Tokugawa era saw a general effort to portray secrets as being associated with false teachings and representing an anti-public spirit. Fueled by neo-Confucian values, the Mikkyo Buddhism-inspired secrecy that permeated so many fields of Japanese culture in the “medieval” period came to be frowned upon during the Edo jidai. Under the Tokugawa, secrets began to be erased from records or simply disclosed in various ways in an effort to throw open the doors and show the integrity of an art or a school of faith by disclosing that which had been a secret before. Secrets were increasingly viewed not as a source of authority and power, but evidence of a hollow core. Disclosing or abandoning secrets was an expression of confidence in the integrity of a practice or tradition. This is a theme persuasively developed in Scheed and Teeuwen’s edited volume, The Culture of Secrecy in Japanese Religion (2006) and particularly in William Bodiford’s essay in that volume, “When Secrecy Ends: the Tokugawa reformation of Tendai Buddhism and its implications.”

Second, this period of time in Japan marked a growing push against Chinese influence. This anti-foreign influence campaign was tied up in efforts to break or suppress the influence of Buddhist temples and elevate the import of Shinto, which was coming to be defined by some as purely Japanese and less pernicious in its political influence and economic power. The reaction to Chinese influence led to a wide-ranging intellectual and educational movement designed to highlight the originality and power of Japanese-based ideas. There are so many sources on these matters it is hard to know what to point to, but I recommend Peter Nose’s Remembering Paradise: Nativism and Nostalgia in Eighteenth Century Japan (1990) and James Ketelaar’s Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan: Buddhism and its Persecution (1993) as good starting points.

These two movements may account for the dropping of written reference to “oral teachings” or “yin and yang” as they fall afoul of either or both Tokugawa values. Shindō Musō ryū had a status as an officially supported art in the Kuroda han. Many of its practitioners served as public safety officers–think police–and would have had to comply with the legal expectations of the Kuroda. This puts our art, via its most accomplished practitioners, under the watchful eyes of Kuroda administrators. Matsui Sensei found records affirming that jōjutsu instructors were recorded in official records as a Kuroda han-recognized position. Receiving a menkyo scroll may have led the recipient to appear before an official of the han to have it recorded, and they may have received a small raise in their retainer’s stipend as a consequence. Matsui’s article points to a Bakamatsu era policy of financially rewarding menkyo as an inducement to have more retainers prepare as fighters. In any case, to a degree that strikes me as unusual for a koryu art, Shindō Musō ryū was an “officially” sanctioned form of bujutsu, which could not be taught outside the han, and its key practitioners were woven into the fabric of the han as retainers using the violent combative techniques of the art under color of law.

So while the Menkyo scrolls of the late 18th and 19th century were documents of the ryu, it is possible they also played a “public” role with (potentially) official review. It was during this same period that the first use of “God’s Way” for Shindo (instead of the original name of True Path or the alternate line’s New Just) came to be used, appearing in that 1781 scroll issued by Inoue mentioned above. In any case, I am proposing that either because authorities directed not to make references in our records to Chinese-tinged secrets, or because savvy seniors could read the times, the kaiden of the late-18th and into the early-19th century simply stopped writing down any reference that would imply secret oral teachings tied to Chinese philosophical or cosmological traditions. Of course there is a small contradiction here, in that the last set of kata is openly named “Secrets”! However, the names of the kata are all plainly written out and anyone inspecting the scroll can see them. Perhaps more importantly, listing a kata set called “Secrets” doesn’t smack of mikkyo buddhism or Chinese influence in the same way that ambiguous phrasing about yin and yang does.

This effect of “official gaze” on the shaping of our ryū’s records is undocumented, but it would be naïve to think that our art may not have been subjected to such pressures. Cultural movements and official tastes have impacted Shindō Musō ryū in very clear ways during the 20th century and there is no reason to believe the art was above such influence in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, I do not know with any certainty why, when or by whom the yin yang references were dropped, and I want to emphasize that my comments amount to nothing more than speculation.

Given the vague 18th century references to oral teachings and yin yang philosophy, do any secret oral teachings remain? All I know is what I was exposed to. When I learned Yamiuchi from Kaminoda Sensei he gave me an oral teaching that resonates with Nagatomi Kotaro’s obscure note about yin yang knowledge from 1768. If what I got is what Nagatomi is referring to, that would mean an oral teaching survived down over 250 years, and if it is consistent with the oral instruction even more vaguely noted by Higuchi in 1720, that would tie us together across 300 years. For an art that is basically a long game of telephone, that would be no small feat. But not only do I not know if the ryū has succeeded in keeping a secret oral teaching unchanged, there is no way to know (barring discovery of an 18th century senior practitioner’s personal notes). Kaminoda’s oral instruction made sense in the context of the kata, and fits with Nagatomi’s vague reference, but all you can do is “believe” it is unchanged as I know of no surviving written record that would prove it, but it may be out there somewhere.

Does everyone get the same oral teaching I got? For those who hear the teaching I received, rooted in old Chinese philosophy, do they understand its significance? To me, I think the teaching invokes an entire chain of theory that most literate martial artists would associate with Chinese internal power arts. The oral teaching also shines light on the widely known shintaku of Muso Gonnosuke, providing a decoder ring-like indicator of the most important way to interpret the admonition “to know the suigetsu.” However, to a modern person, the teaching could easily be passed over as just poetic words or a childlike mnemonic device.

My experience leads me to doubt that all who hear the words consider them important. I have been told of two menkyo who do not remember hearing a phrase or invocation at all. Perhaps the phrase seemed trivial, or they were so focused on observing and copying the movements of the kata that the words did not really register? Speaking only for myself, the moment of learning the secret kata is full of emotion and pressure as one is aware of what an honor it is and also the reality that this may be the only time you are ever shown the kata so you either get it in this moment or you lose the opportunity! Given the weight of the event, it would be understandable if some might come away without a clear memory of what was said as the focus is on what you should be doing with your body.

Another possibility is that some teachers did not get the oral instruction themselves, or decided not to share it when it came time to teach a student the Gokui. There are many reasons a kaiden might choose not to give this teaching to a student. They might judge that the teaching would do nothing to change or enhance that student’s art. More probably, a teacher could decide to simply let the teaching go as meaningless in a modern world given the current focus of most people’s jōdō. Look at Christopher Li’s (of the Sangenkai Aikidō in Honolulu) writings about the cosmology teachings underlying Ueshiba Sensei’s aikidō. Many of Ueshiba’s philosophical flourishes were dismissed by some deshi as nonsense, though the cosmology and mythology he invoked was Ueshiba’s way of trying to provide a roadmap to the physiology of what he was able to do. Now shift your awareness to my art which is 15 to 20 generations old. Is it surprising that some modern lines, or some teachers, may have lost or simply dropped the secret teaching? Maybe more surprising is that anyone has maintained the words.

So we have secrets that everyone thinks they know–the shintaku of Musō; we have secrets everyone knows exist but few ever learn–the five kata; then we have an oral secret associated with the first of the Gokui kata. The core oral teachings of the ryū are supposed to be captured in the shintaku of the founder and then in the teaching associated with Yamiuchi. I can say that the teaching has absolutely no impact on performing the kata at a very high level for ZNKR rank or in maintaining and polishing the kata if that is the orientation of a Shindō Musō ryū koryū group. At their core, the teachings are about preparing a fighter to use a staff to defeat a swordsman, so the words that should be a treasure of the school are as relevant to most people’s jōdō as the randori or use of steel blades I wrote about in my first essay on secrets. Yet if you climb to the top of the greasy koryū pole, you may find an invocation awaiting you tied to yin and yang. That suggests something important about what we should be developing in our practice of Shindō Mūso ryū, and what we should be passing on as well.

That is as much as I feel I can say about our secrets, and I would understand if some feel I have said too much.