It would be impossible to exaggerate the importance of Shimizu Takaji Sensei in popularizing Shindo Muso ryu. The essence of his story is that he receives Menkyo kaiden in his early 20s, moves to Tokyo in 1930 with encouragement from Kano Jigoro, Nakayama Hakudo, and Suenaga Misao. In Tokyo, he teaches jodo full-time, becomes an instructor at the Kodokan and is invited to train a newly formed Tokyo police riot squad. He invents the kihon–basic exercises–to simplify the teaching of the essence of Shindo Muso ryu to large numbers of students. By 1940 he has written a book on jodo, has established students in Manchukuo, and moves in circles with the most powerful political figures and martial artists of the era. He is almost single-handedly responsible for reshaping Shindo Muso ryu from an old-fashioned jutsu, into a sleek, modern “dou” (jodo) now practiced on six continents. (Mark Tankosich ably covers Shimizu’s activities in creating and spreading jodo in his article, http://www.marktankosich.com/path-zen-ken-ren-jodo-abbreviated-history-shindo-muso-ryu-advent-modern-offshoot/.)

In 1941, Shimizu finds a venue for his art in a popular culture magazine aimed squarely at mobilizing young men to prepare to fight for their country. That magazine, “Shin Budo”, provided a vehicle for Shimizu to prove to his political and financial supporters that he could serve the national interests, while simultaneously spreading awareness of his new art. This article will share what he showed of his kihon in the pages of “Shin Budo.” I will argue that his kihon at that time were not just about modernizing jojutsu by using rational teaching principles to organize essential movements into basic exercises. Jodo was that, but it was something more to meet the historical moment. By 1942 his kihon began with a core set of skills supporting national mobilization for war that were not derived from Shindo Muso ryu, and that this “jodo plus” was Shimizu’s marketing hook for spreading jodo.

“Shin Budo” (New Budo) first appeared in April, 1941 and its editorial message tried to draw a clear line of continuity between the mythologized values of the samurai (“bushido”), surviving koryu arts (and their gendai offshoots), and modern military training. Japan had already been at war for a decade in China, had created the dependent state of Manchukuo as a cornerstone for its vision of a Japan-dominated economic and cultural sphere of influence in Asia, and was experiencing rising tension with both the U.K. and the U.S.A. This is the context that informs the content and the intentions of a magazine clearly aimed at building popular interest in supporting the nation through whatever storms lie ahead.

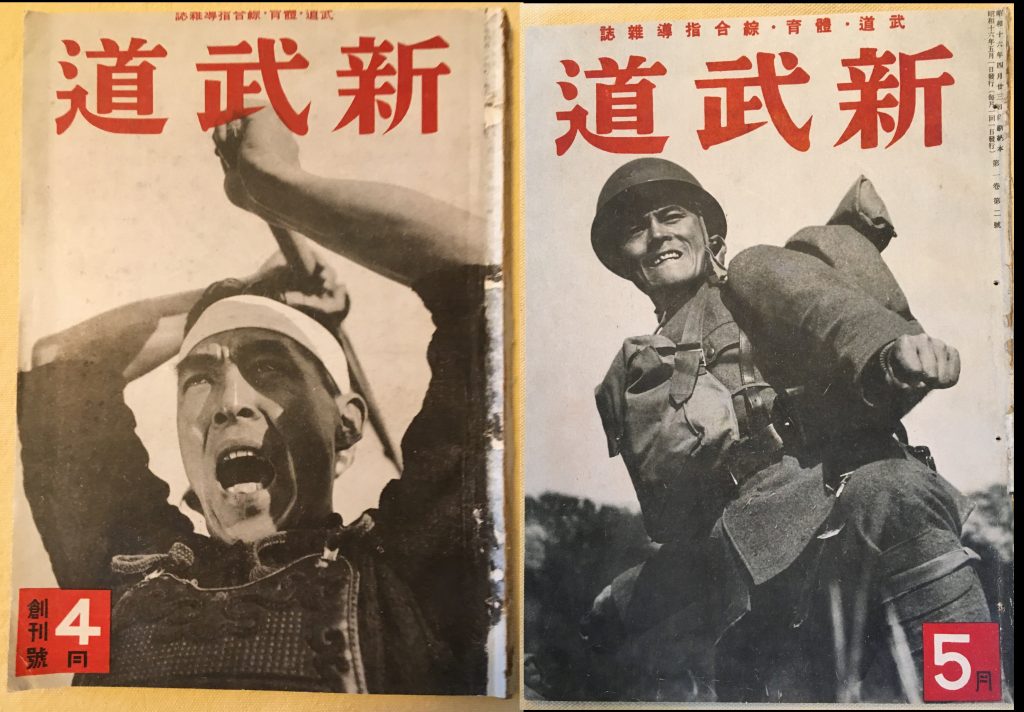

The covers above are from the first two editions and neatly convey the range of material that infused the magazines. The cover of volume #1 (April, 1941) shows a black and white photo of a Japanese kendoka holding his shinai in a jodan kamae, his dou (chest plate) is visible. He wears a hachimaki (headband), mouth open in a loud kiai, he is prepared to strike with his shinai. The cover of volume #2 (May, 1941) shows a soldier in full modern army kit circa 1940. He is also in a kind of kamae, kneeling on the ground with his body coiled in preparation for a proper grenade throw. Both volumes have the name of the magazine, “Shin Budo” (written in traditional form of right to left 道武新), in vivid red ink floating over the black and white cover image.

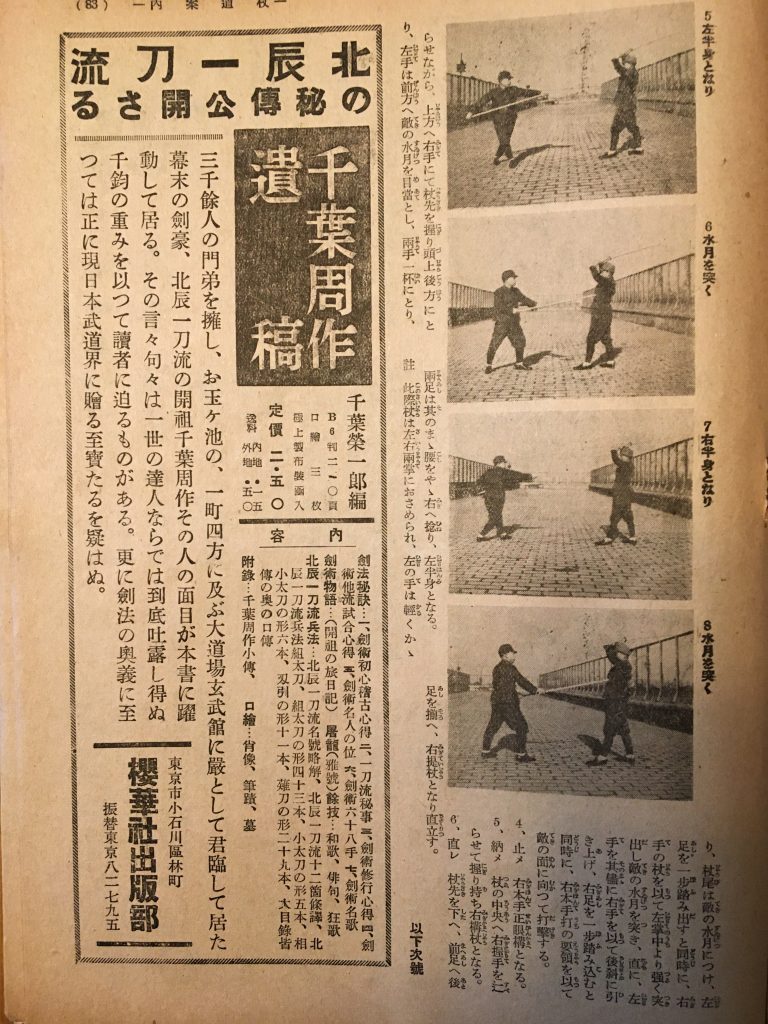

The publisher and chief editor of “Shin Budo” was Takano Hiromasa, an important figure in the Japanese budo world as he was the second son of the legendary kendoka, Takano Sasaburo, and was himself a highly ranked kendoka, well-known teacher, and head of the Itto ryu sword school. His presence at the masthead of “Shin Budo” symbolized the significant commitment of the Japanese budo community towards contributing to Japan’s war effort. Notably, the magazine is itself a publication of the National Defense Martial Arts Association (国防武道協会), which was certainly sponsored and organized by the government. Each edition combined discussions of world affairs, battles, historical Japanese heroes, profiles of particular martial arts (often with some “how to” quality) and long debates about the role of budo in ensuring Japan’s wartime success. This was “Shin Budo” as it was launched in 1941 and its target audience was middle-school and older Japanese boys.

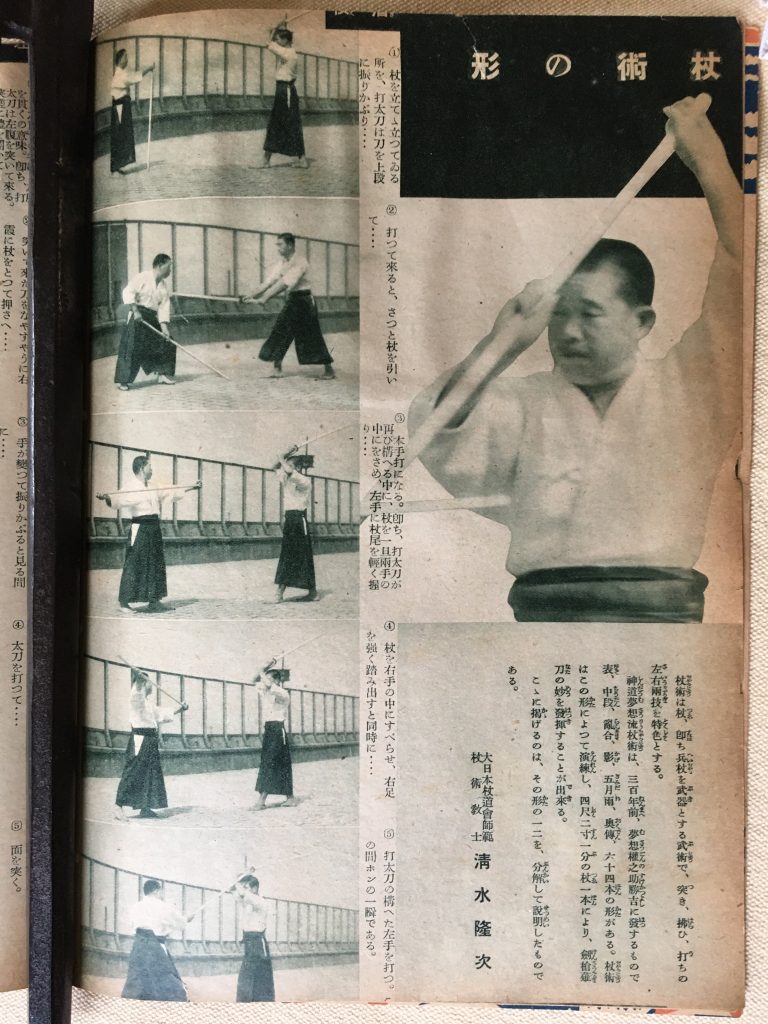

Shimizu Takaji Sensei was given a prominent and ongoing role in the magazine in its first year. His name appears in the very first edition as an editorial advisor (there were dozens). Then, he is introduced to the readership as an important martial artist in the 8th issue (November, 1941). The magazine profiles Shimizu in the high-quality photo gravure section included at the front of each issue. Shimizu Sensei appears in that volume with an unidentified partner showing three kata: Tsukizue, Sakan, and Kengome. Each kata gets five action photos. The article is titled “Jojutsu kata” (杖術の形)–not jodo. Beneath the title is a photo of Shimizu Sensei from the Sakan sequence. There is a small box with text explaining that the art of Shindo Muso ryu jojutsu is 300 years old and contains 64 kata. Shimizu Sensei is identified as the head of the Dai Nippon Jodokai–the organization he launched in 1940 with the backing of Toyama Mitsuru–and a jojutsu kyoshi. The title “kyoshi” reflects the rank award he received from the Dai Nippon Butokuden (DNBK) in 1930. (Note that this is not the first jodo magazine series for Shimizu as I believe he had a monthly column in the magazine of the Kodokan, but that was not a mass marketing, popular culture magazine.)

While the photos are pretty good, with accompanying text of what each side is doing, I do not think someone lacking training in the ryu could actually recreate the kata as Shimizu Sensei shows them from the photos and descriptions. Too many steps are missing or ambiguous. Compare the five photos for each of these three kata to the 1976 Jodo Kyohan treatment of these kata which uses 15 photos (Tsukizue), 19 photos (Sakan), and 13 photos (Kengome) respectively to aid in demonstrating the performance of the kata.

Looking carefully at Shimizu Sensei he is dressed in an unfamiliar way, at least to my eyes. Here he has a white uwagi and a blue or black hakama. His himo is tied in a different fashion with the knot being made at the back of his uniform (outside of the koshita), not the front. His aite appears to be in the same uniform. Both he and his aite are barefoot and they are working on what looks like a stone courtyard or roof surrounded by fencing.

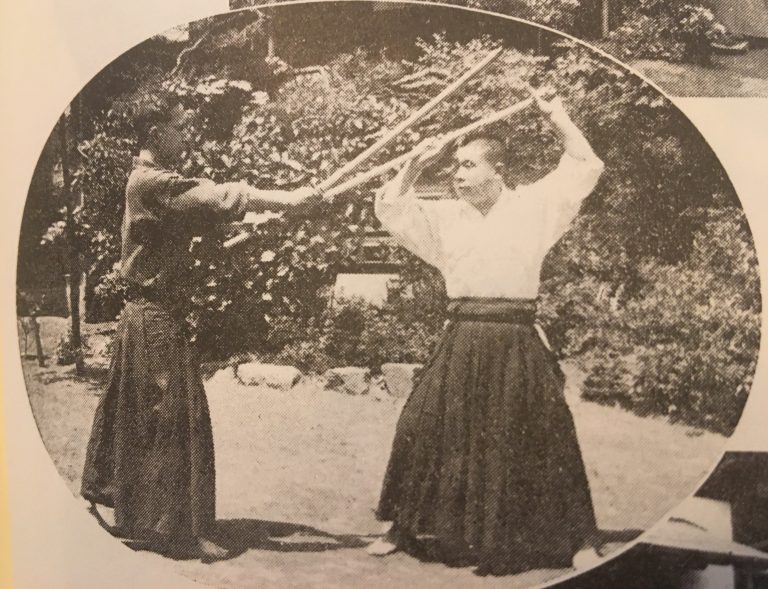

This style of dress is the same that Shimizu shows in the photos from his 1940 book promoting his kihon. I have the 1988 republication titled “Jodo Kyohan” and the photo below is from that copy. The text of the 1940 volume was aimed at both the Manchurian audience and the domestic Japanese audience, and encourages Japanese people to get a partner (husbands with wives, etc.) and begin practicing jodo. The 1940 volume was the first textbook on jodo or jojutsu that I know of, though Shimizu had begun publishing student manuals that included his kihon as early as (at least) 1937.

In any case, what we think of as the “traditional” costume for Shindo Muso ryu–with white hakama and uwagi being used largely in the Fukuoka line and the blue hakama and uwagi of the Tokyo line–was clearly not the uniform Shimizu Sensei preferred at this time. His is something of a mash-up of those styles, but the arrangement of his himo is definitely different from anything that I have seen in photos from the last 60 years. I linger on this point as it powerfully illustrates that what any of us in the ryu think of as “traditional” is largely a function of what your teacher told you to do. In a 400 year old art, there have been lots of changes to “tradition,” including how we dress.

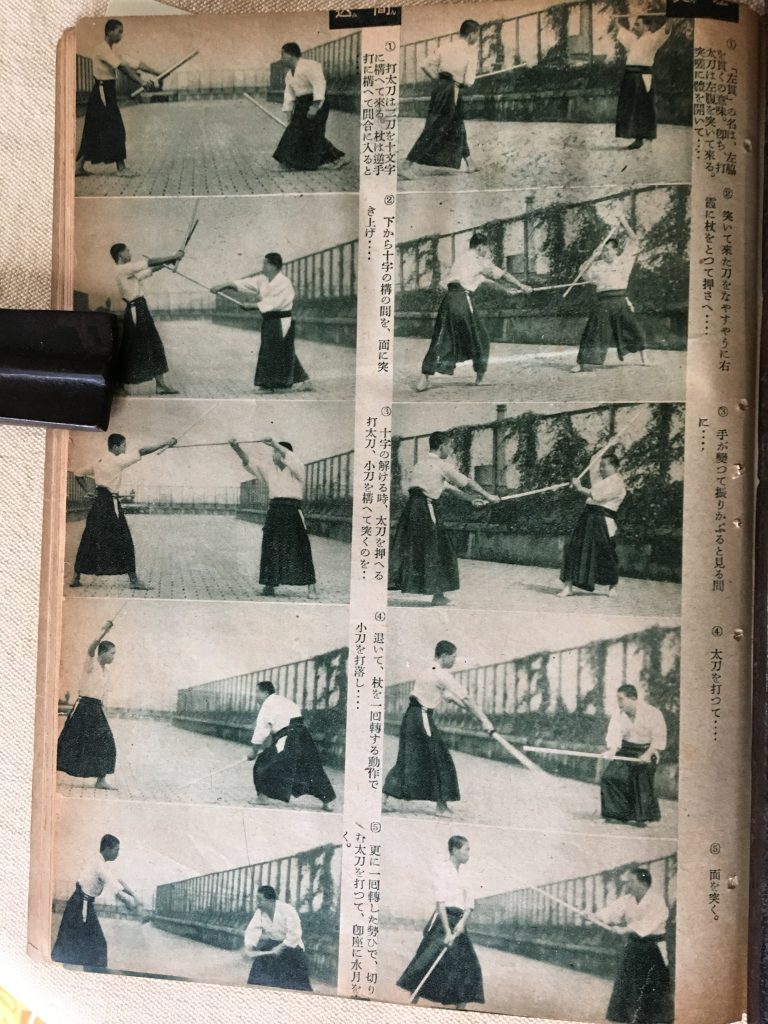

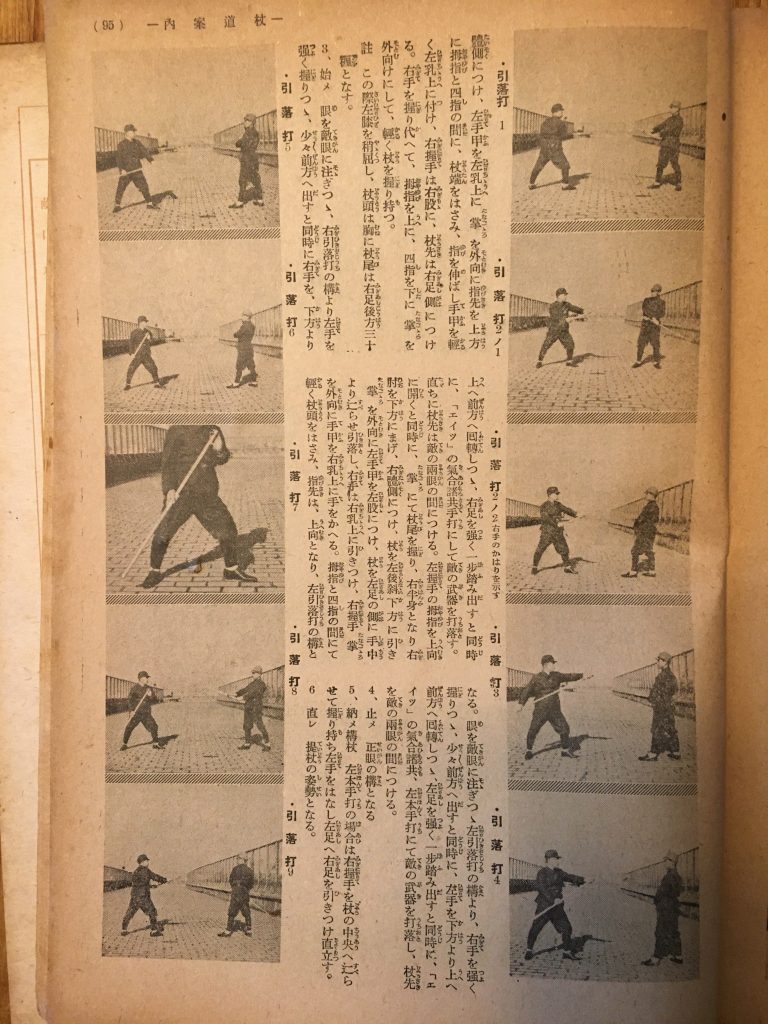

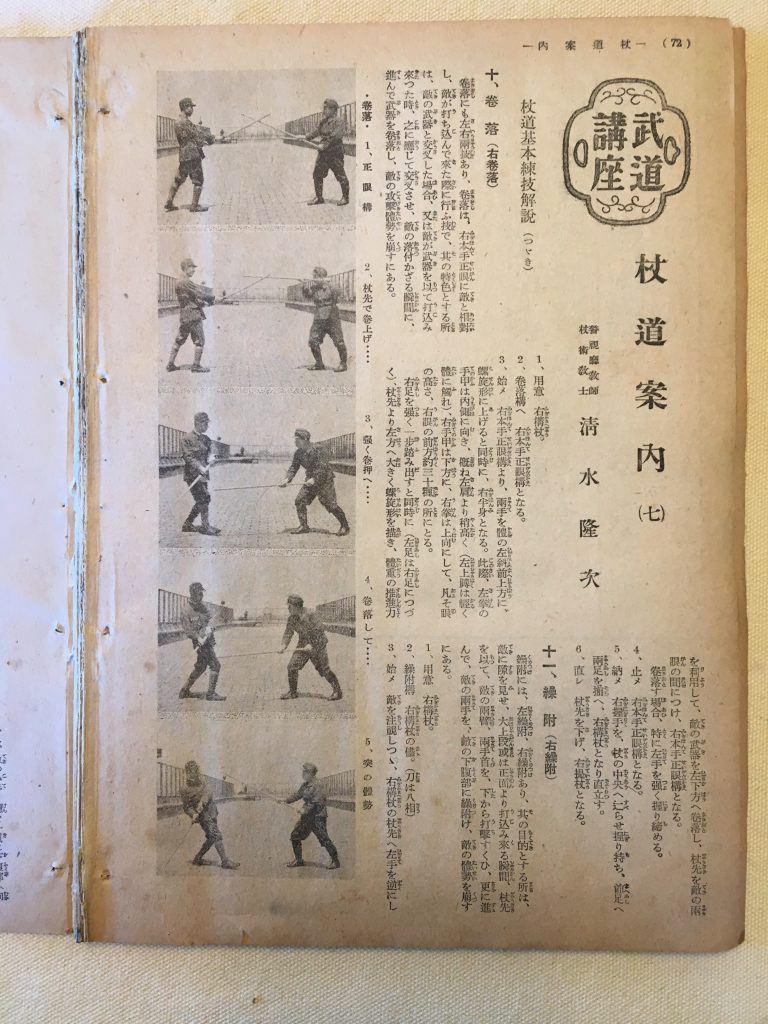

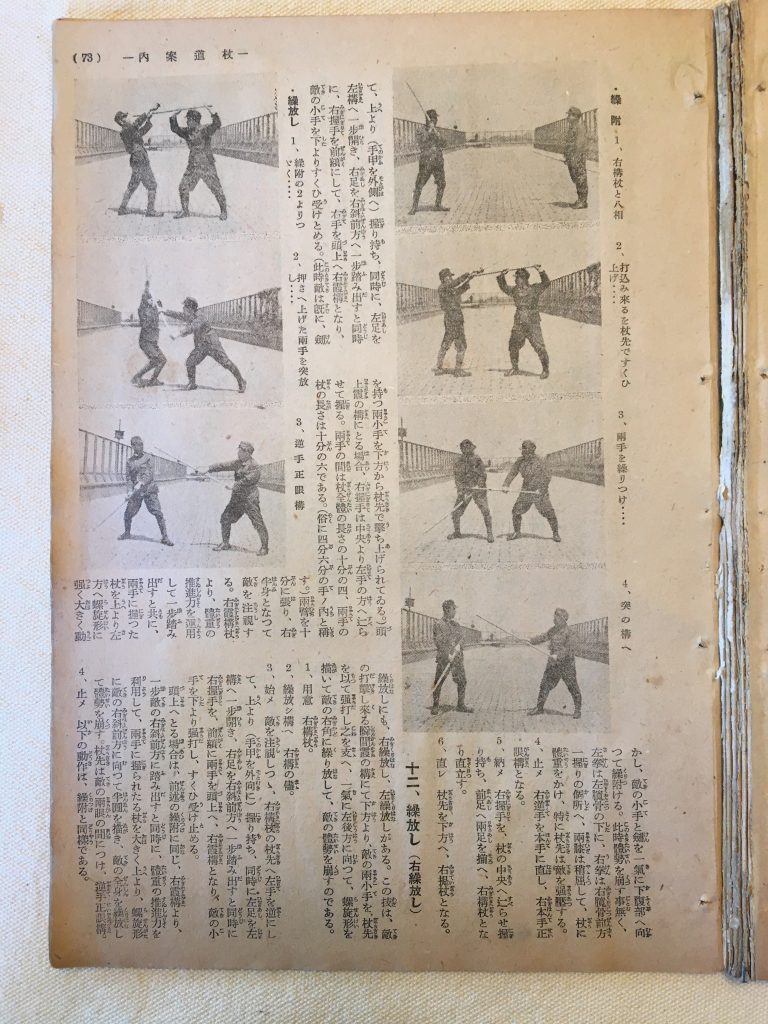

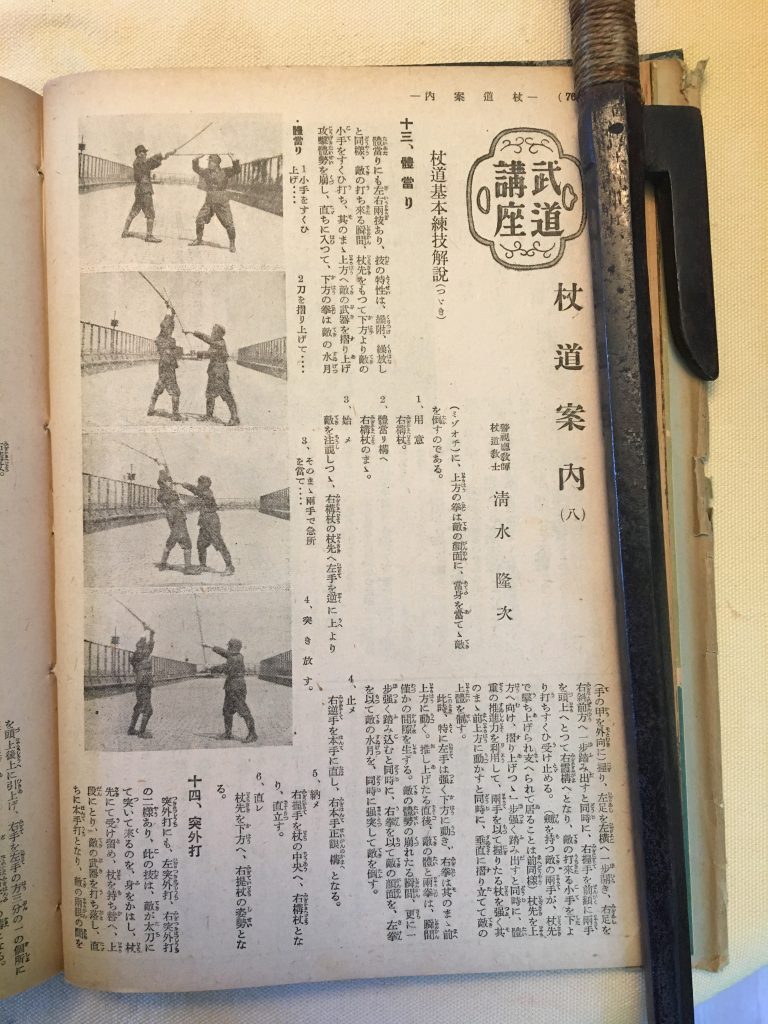

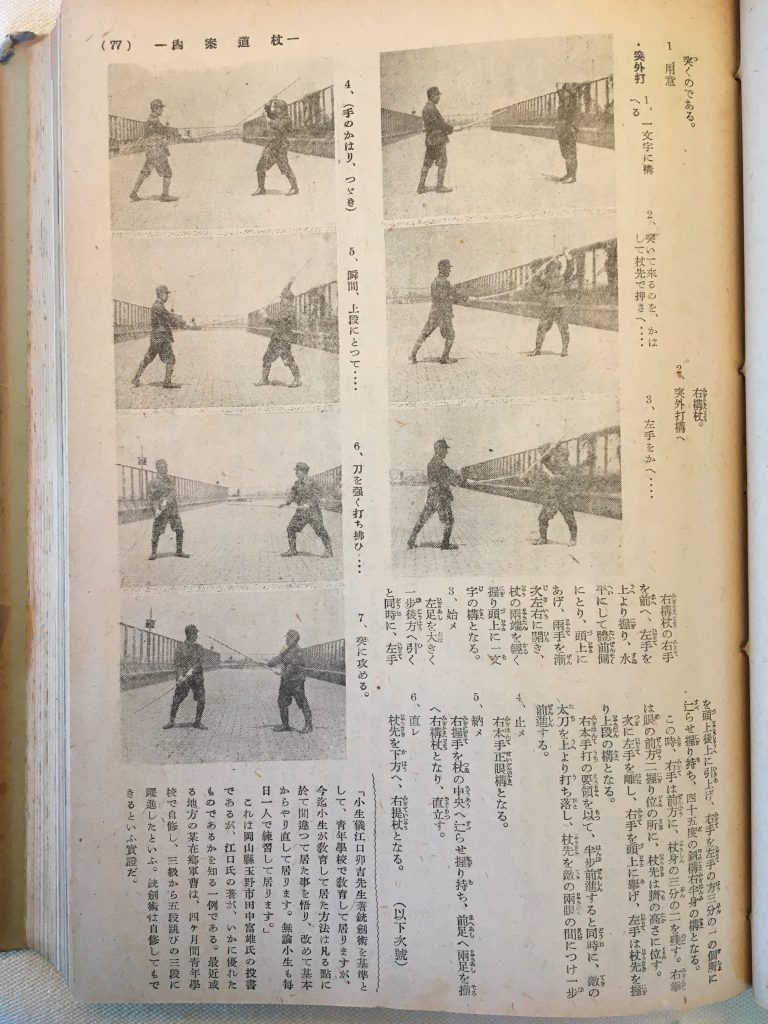

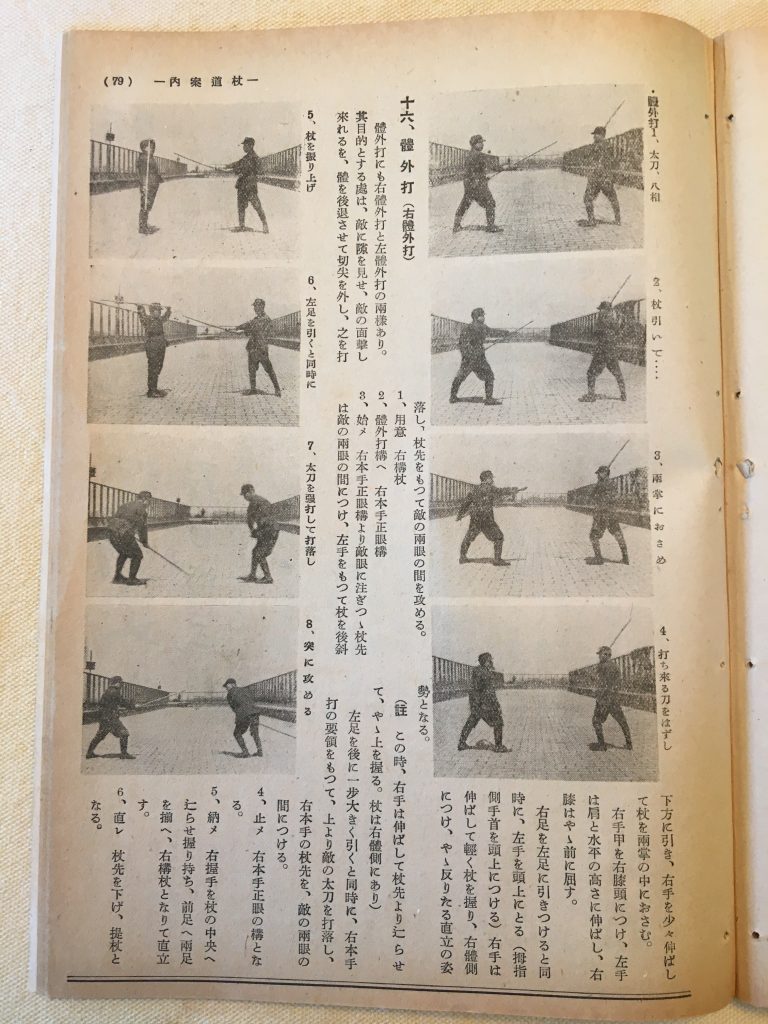

Beginning with the next issue of “Shin Budo” in December, 1941 and continuing on through to August, 1942, Shimizu contributes 9 brief articles about jodo and jojutsu. Beginning with the March, 1942 volume, Shimizu begins a “how to” series that touches on each of his kihon and this continues through the August, 1942 edition. Each kihon is accompanied with detailed descriptions of what the two practitioners, jo and tachi, should be doing, and in most cases there are accompanying photographs illustrating the moves. Note that all the kihon shown in the photos from these magazines are done as partnered practice.

The images reproduced below are from the March, April, May, June, July, and August 1942 editions of “Shin Budo.” I list the names of the techniques as translated from the magazine’s text. I have chosen to reproduce these in a large format to let people examine the documents for their own purposes.

March, 1942

March 1942 introduces 5 techniques (1 and 2 appear to be variations of each other and very like a kendo exercise; 3 and 4 appear to be variations of each other and very like a jukendo activity).

- Shomen Uchikomi; strike from jodan to head of tachi.

- Sa Iu Naname Uchikomi; no photos–it appears to be cuts from jodan with tachi stepping back to receive the strikes on the diagonal to the left and the right.

- Tsuki; no photos of this technique but the description can be read as: “From seigan no kamae, stab to the enemy’s throat.” Seigan is shown in the first photo of the next technique at the bottom of the first page from March, 1942. It is similar to honte no kamae, but in this case the rear hand is held back on the hip and the back foot/hip are pulled back a little more than would be the case if in honte.

- Choku totsu (totsu is the same kanji as “tsuki”) jo makes a straight thrust to the heart level of tachi. I believe the description reads, “This straight thrust is the same as the bayonet move used by the military in which the enemy is struck on the left side of the body to the heart.”

- Honte uchi; most extensive photos. First kihon that is recognizable as such to modern eyes.

April, 1942

6. Gyakute Uchi

7. Hikiotoshi Uchi

May, 1942

8. Hineri goshi tsuki (twist, waist, thrust); the modern name is kaeshitsuki.

9. Gyakute tsuki. There are no photos of this form, so I am not sure someone would be able to accomplish it based on the text alone.

June, 1942

10. Makiotoshi

11. Kuritsuke

12. Kurihanashi

July, 1942

13. Tai atari

14. Tsuki hazushi uchi

August, 1942

15. Doubarai uchi (note the editors failed to insert kana, making reading much less reliable).

16. Taihazushi uchi.

So there you have it, 16 kihon (although a couple are variations on the same move). Shimizu’s kihon had been in flux since at least 1931, but 16 is the high water mark I know of, and even with a lot of overlap to the kihon of the 1940 Jodo Kyohan volume, the order differs somewhat between the two sources–and that rearrangement came in less than 2 years time.

Some of the moves shown in “Shin Budo” are not familiar to those of us who have come to inherit the 12 kihon that were firmed up as the ZNKR-approved kihon. Exercises 1 through 4 seem to be a concession to the army’s value of the use of sword (cutting from jodan) and bayonet (high thrust to the throat or heart). The moves as described are not derived from the kata of Shindo Muso ryu, and the fact that they are included here as the very first kihon tells us something about Shimizu’s marketing savvy. Shimizu built his jodo kihon starting with moves that provide nothing of inherent value to learning Shindo Muso ryu, but everything to do with satisfying the military-centric budo values of contemporary Japan. To put it bluntly, if Shimizu is going to spread his jodo he has to show that it supports the military needs of the Japanese army by preparing young men as potential soldiers. Cutting from jodan represented the essence of Japanese army swordsmanship. As for bayonets, from 1907 on to the war, the Imperial Japanese Army’s manuals on infantry tactics always emphasized the importance of cold steel and the bayonet charge in determining victory. The sword of officers and NCO’s and the bayonet of line troops represented the spiritual and practical core of IJA battlefield combat theory. Shimizu appears to be responding to the Army’s “need” with his kihon, and any young person learning the jodo kihon at that time would come away with a basic functional skill for cutting with sword or stabbing with a bayonet.

In that context, you can appreciate that these kihon were not about teaching Shindo Muso ryu to big groups, but provided a ready set of core “budo” movements that would be relevant to wielding a sword, a rifle with bayonet, or a staff. His kihon were all-purpose exercises and so his “jodo” circa-1940 was not simply a modernized jojutsu (though that is in the set too). You can argue that “cuts” from jodan and stabbing the heart or throat exist in Shindo Muso ryu, and I don’t deny that, but you have to squint pretty hard to make these kihon fit with Shindo Muso ryu practice. The fact that these sword and bayonet moves all get dropped in the post-war period, leaving us the 12 we have (all of which are in place for this “Shin Budo” series) seems to support my view that Shimizu’s jodo in 1942 was designed to meet a broad range of martial goals and not just inculcate essential movements from his koryu art.

To my eyes, Shimizu’s stance across these kihon photos looks odd at times (and his aite is alternatively stiff-legged and upright or breaking his balance with a cut or thrust), though Shimizu’s posture in the jojutsu photo shoot of November, 1941 appears “normal” to me. Is the footwork and posture of the kihon photos “old jojutsu” simply applied to the new jodo mold? Or was this Shimizu altering teaching to try to conform to stances and moves that fit better with the contemporary expectations of kendo and jukendo, the dominant young men’s militaristic weapons arts? I am guessing it is mostly Shimizu’s effort to make his jodo palatable to peers and influential benefactors who saw things through a lens largely shaped by kendo, battodo, and jukendo. It also meant that his teachings would not contradict the habits and practices of young people coming through military-dominated kendo and jukendo training.

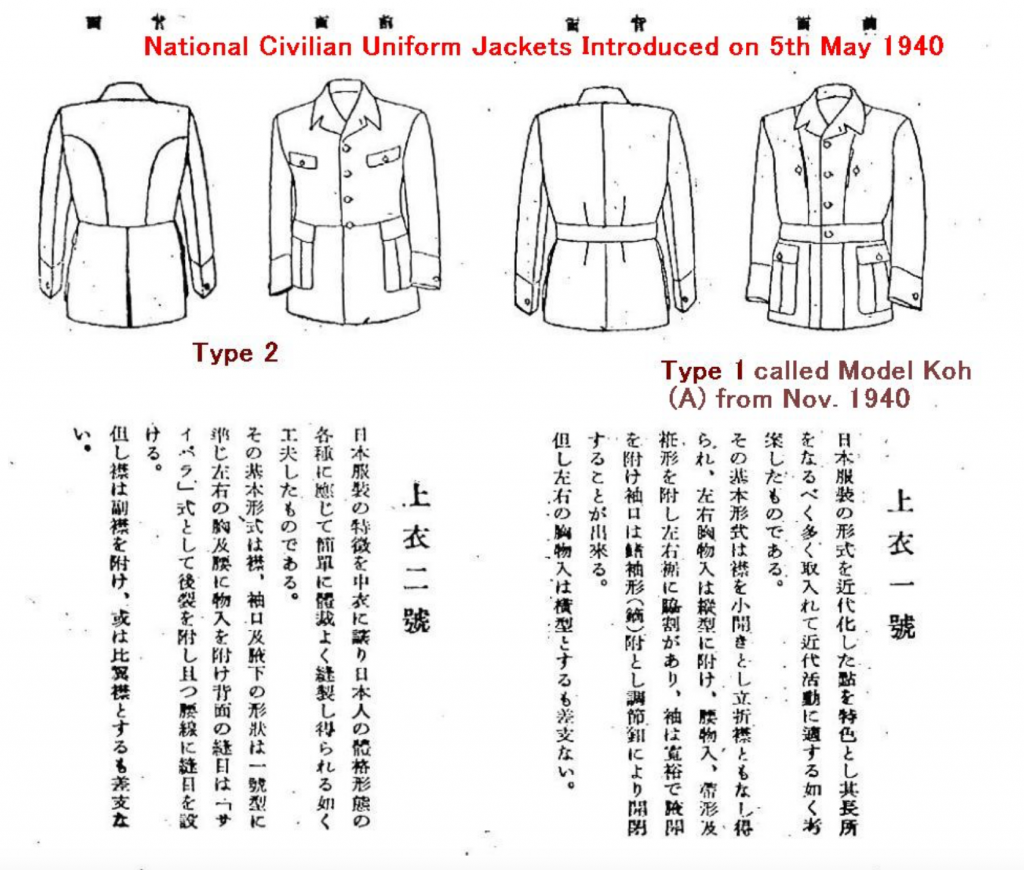

As for uniforms, all the images from the series on jodo kihon show the kihon being done in what may be a police uniform, but could also simply be contemporary men’s dress; this was the Kokumin fuku outfit that was patterned on the army’s tunic and made in any color you wanted as long as it was something combining green, brown, and gray. This militaristic cut of jacket, pants, and cap had been proclaimed (by Imperial Edict!) as the national form of dress for men in 1940. The image below is from research done by the late Nick Komiya, who conducted years of work into Japanese military gear and policies. His discussion of the Kokumin fuku is available here: https://www.warrelics.eu/forum/japanese-militaria/national-civilian-uniform-1940-a-677200/ His contributions to discussions on that forum (including gunto sword research) is indexed here: https://www.warrelics.eu/forum/japanese-militaria/master-index-reference-articles-written-nick-komiya-691796/ .

Whether Shimizu is wearing his Kokumin fuku jacket or perhaps a police uniform is hard to discern in these pictures as the tunic and leggings of the popular clothes are virtually identical to the army uniform and probably the police uniform as well. This style of dress was common already in school uniforms. The students, scouts and young martial artists the magazine was aimed at would certainly have felt at home seeing the “military” uniform of the day as dress for practicing a modern martial art.

The text accompanying the kihon photos clearly identifies the activity as “jodo” in contrast to “jojutsu.” Shimizu is actually a perfect representative of the philosophy of “Shin Budo” magazine as he can seamlessly move from classic koryu bujutsu associated with the samurai (as portrayed in “Shin Budo’s” November, 1941 photo essay on Shindo Muso ryu jojutsu) to a modern fighting practice associated with the famous special police squad that he trained in Tokyo. Following his specific guidance a young reader could begin to train in the same way, and their school uniform or scout uniform would be perfectly attuned to this new art. The shift in his uniform accentuates the two distinct roles he embodied, but marks jodo as essentially modern.

After that August, 1942 sequence, I cannot find Shimizu participating as an author in any more editions of “Shin Budo” (it is hard for me to get access to issues from 1944). It may be that the series came to a natural end at that point, although one could imagine a more complete treatment of solo kihon and perhaps more detailed kata as well if there had been editorial support and interest. The termination of the kihon series comes at almost the same time that the magazine was being pressured to take a new editorial direction focused on pragmatic training in bayonet and marksmanship.

More on “Shin Budo” to come..