Articles carried in the wartime magazine, Shin Budō, give us insight into Shimizu’s emerging art of jōdō. Following the glossy pictorial treatment of Shimizu Takaji and Shindō Musō ryū jōjutsu in the November, 1941 edition of Shin Budō, Shimizu launched a series on the basic kihon practice of his jōdō. I have already addressed that initial November, 1941 article, and then the subsequent display of kihon contained in the January 1942-August 1942 issues of Shin Budō in Part I. The December, 1941 issue, which is covered in this piece, offered a three page essay by Shimizu regarding jōjutsu and jōdō; it is a hinge that ties the November jōjutsu-focused profile of Shimizu Sensei as a master of a koryu art to the kihon instructional articles by the creator of jodo. What follows is a loose translation of Shimizu’s essay.

The December, 1941 edition of Shin Budō stands out as being the only edition in its first two years of publication that profiles women on the cover. Reproduced above, we see three young Japanese women at the end of a sprint race. It is a beautiful photograph for its unstaged, natural energy and the full physical effort of the young women. There is no indication of what kind of event this was, though the women wear singlets that appear to signify at least two different teams, and all of them are wearing spikes. That and the men in the stands (two of whom also appear to be in track uniforms) suggests this is not a casual event. Shimizu’s article in this issue includes a short section aimed specifically at women doing jō, but whether that was a “tie in” with the cover or pure chance is unknown. Nothing else in the magazine suggests a focus on women in budo.

The larger context of Shimizu’s article is important: Japan was in the middle of a war and the government had been captured by the military. Every segment of Japanese society was being “mobilized” to support the war, and the inculcation of “traditional” budō values in the context of martial training was an important part of that officially-sanctioned mobilization. Shimizu is writing an article in a magazine supported by the government, with an editorial board composed of officials and military officers as well as well-known martial artists. This is not a casual article about things that are going on in his effort to create jōdō, but an article designed to garner attention to the role that jōdō could play in meeting the national mobilization goals of a government on the edge of global war.

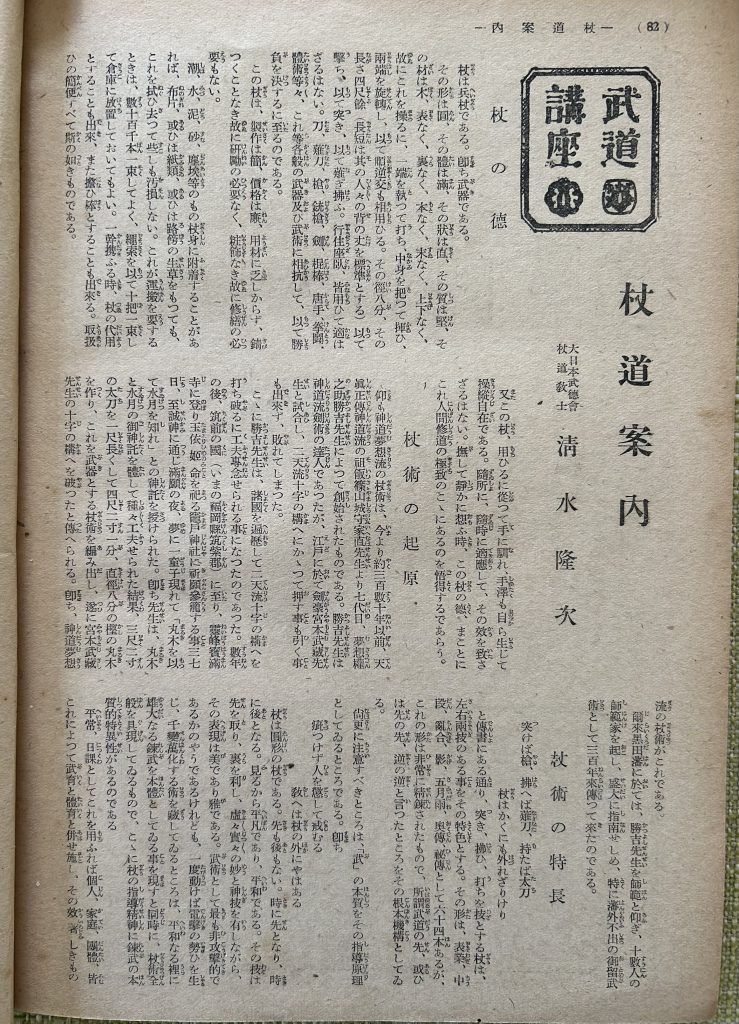

The article itself appears on pages 82-84. I am not claiming that I have produced the best translation that could be done of his writing (hoping that someone with appropriate 1930s Japanese translation skills will tackle this, and including good images of the original article), but I want to try to communicate the essence of what he wrote and hope I do it justice. In translation, I have taken editorial liberties to rearrange some of the material to create more continuity for the reader, without doing injustice to Shimizu’s meaning. The article is framed by editors as a part of a “budō course,” foreshadowing the subsequent kihon instructional articles.

Guide to Jōdō

by Shimizu Takaji, Dai Nippon Butokukai jōdō kyōshi.

The Virtues of the Staff

The staff is a weapon. It is round in shape, always ready, straight, solid, it is made of wood and lacks a front or a back. It has no top or bottom. You can grab it, punch with it, rotate it around end over end. It can be used in both forward and reverse directions. It is 4 shaku in length and 8 bu in diameter and this is the standard for tall people and short people. The staff is versatile, you can strike with it, stab with it, sweep with it. Of course the katana, naginata, yari, bayonet, double-edged swords, clubs, karate, boxing, jujutsu and so on all have their own traditions and their own place in the coming battle. As for the staff, it is simple to make, inexpensive, and there is no shortage of materials. Since the jō never rusts it does not require sharpening or special care, and lacking fittings it does not need repair.

If a staff is exposed to sea air, or water, mud, sand, dust and so on, just wipe it off! Use a cloth, a piece of paper, or even fresh grass from the roadside. It won’t make the staff dirty in the slightest. To transport it, you can store hundreds of thousands in a warehouse, or just tie ten together with a rope. When carrying it, it can be used as a hiking staff or a tool Handling it is as simple as this.

The cane easily fits the hand, and the hand develops its own grip allowing the staff to be used freely in a variety of ways. You can use it anywhere at anytime. After you have used the staff for a while, and deeply reflect on the experience of the art, you come to understand that the staff represents a very pure martial discipline.

The Origins of Jōjutsu

Shindō Musō ryū jōjutsu was founded about 300 years ago by Muso Gonnosuke Katsuyoshi Sensei, himself the 7th generation from the founder of Tenshin Shintō ryū, Ienao Sensei. Katsuyoshi Sensei (ed. this is Shimizu’s naming) was a master of Shintō ryū kenjutsu, but in Edo he had a match with Musashi Miyamoto Sensei. Katsuyoshi was trapped in the Niten ryū jyūji (ed. crossed sword block), unable to push in or pull back, and he lost.

Katsuyoshi Sensei then travelled the country striving to find how to break the Niten ryū cross block. Several years later, he reached the province of Chikuzen (ed. contemporary Fukuoka prefecture), climbed the sacred Hōman mountain and prayed for 37 days at Kamadō Shrine. In a dream, a young boy ( ed. 一童子) delivered a divine message (ed. Shimizu uses “Shintaku”神託): “Maruki wo motte, suigetsu wo shire”–with a round stick, know the suigetsu. This led him to take a round, straight oak staff 1 shaku longer than a standard tachi. Then he created staff techniques that allowed it to be used as a weapon to break Musashi Sensei’s jyūji block. This became the jōjutsu of Shindō Musō ryū.

Later, Katsuyoshi Sensei became an instructor in the Kuroda han and passed his teachings to 10 masters, that he taught extensively. For 300 years this art was kept by the Kuroda as an oteme bujutsu–that is an art exclusively retained as a secret of the retainers of the Kuroda.

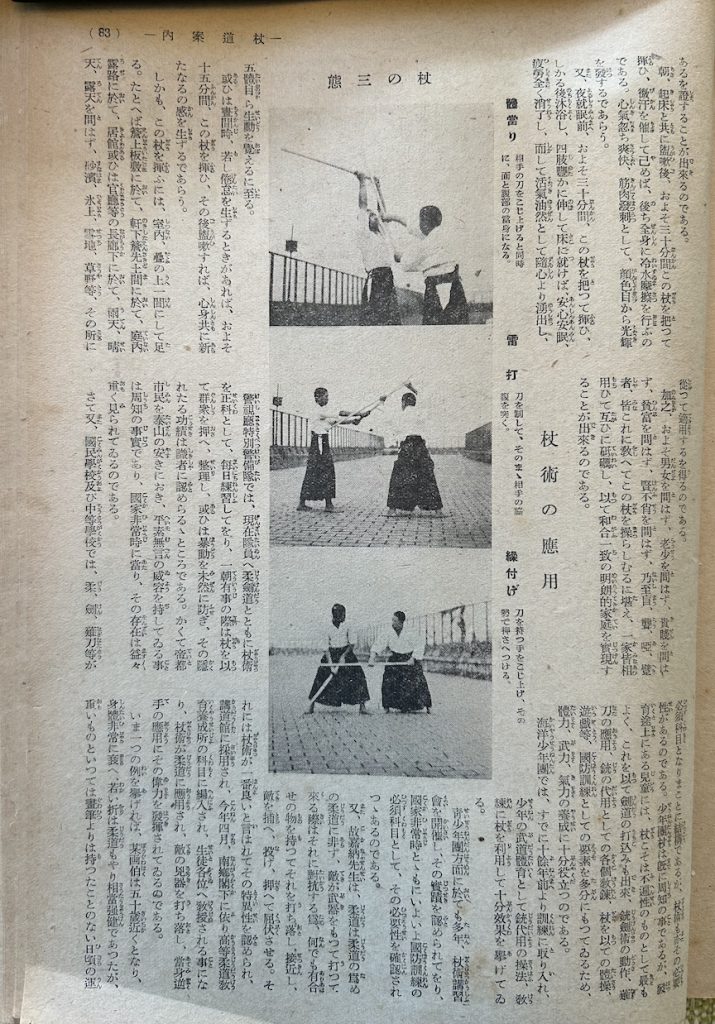

Features of Jōjutsu

Stab and it is a spear. Sweeping, it becomes a naginata. Holding it as a sword, it cuts. As recorded in the densho of the ryū, the staff can stab, sweep, and hit and its techniques can be used from the left or the right and this is a special quality of the staff.

Jōjutsu has 64 kata contained in the omote, chūdan, ranai, kage, samidare, okuden, and hiden sets. The kata are extremely refined. The staff’s ability to take the initiative (ed. sen no sen) is beyond that of other budō, and it can be used end over end in a unique way. This represents a fundamental technique of jōjutsu.

It is very important to recognize that Shindō Musō ryū uses the very essence of “BU” as its guiding principle. Nothing surpasses a round staff in its capacity to defeat, discipline, and admonish without causing permanent harm. In an exchange, the staff can move first, but it can also wait and then respond. The weapon looks unthreatening, but the techniques emerge instantaneously, and can take advantage of the weapon’s “back” (ed. note, this is a way of saying that all the jō is an effective weapon). Seemingly simple, the reality of the weapon is that it draws on mysterious, divine techniques. The expression of jōjutsu is beautiful and elegant, and although it seems to be the least aggressive bujutsu, once the staff moves it generates an electric shock force with infinite variations in technique. In the hand, the staff and the player transform to embody the entire range of techniques, and this reveals jōjutsu’s unique capacity to polish a martial spirit.

Used in a daily routine, individuals, families, and groups alike will find this practice extremely valuable, especially if done in combination with other martial education and physical education.

In the morning, I wake up and (after washing my mouth) I pick up the staff and wield it for about 30 minutes until I work up a light sweat. Then I rinse my whole body in cold water. Immediately, my mind is refreshed, my muscles feel alive, and my face is glowing. To help sleeping at night, take your staff and use it for about 30 minutes. Then take a bath and fully wash. You will sleep peacefully, getting rid of all fatigue, and wake up refreshed. Through these practices your energy springs forth, pouring from the heart, and you can draw on that energy as needed.

Through jo I have learned to feel the movement of my whole body. If you are tired, wield the staff for about 15 minutes, rinse your mouth, and this will refresh your mind and body. Of course you can practice indoors on a tatami mat, but you can also be on a wooden floor under the eaves, on an outdoor garden path, in the long corridor of a government building, in sand or grass fields, outside rain or shine, snow or ice. The jo requires no special space or conditions and can be used anywhere.

All men and women, old and young, with no limits on status or wealth, whether educated or not, blind, deaf, mute, other-abled–all can be taught to use the staff. Perservering together, the whole group can work, as a family, to endure the hard training and create a bright and harmonious atmosphere of unity.

At the Keishichō Tokubetsu Keibitai (ed. note the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department Special Security Guard was the riot police unit that Shimizu Sensei was hired to teach), current members practice (ed. Shimizu uses “renshu”) jūdō and kendō every day. Jō has been added as a part of the training. The cane can be used to control a crowd–to push and organize it–avoiding riots. The achievements of this unit, while largely hidden, have been recognized by experts. Thus the citizens of the Imperial City remain in a condition of perfect security, allowing them to live their lives in quiet dignity and to flourish even in a time of national emergency.

Currently, Kokumin Gakkō (ed. these were elementary schools that had been reorganized in 1941 for nationalist training of youth) and middle schools have jūdō and kendō and naginatadō as required subjects and this is a good thing. However, jōjutsu should also be a mandatory subject. Boys jō (shonen danjō) is already well known. For youth, the jō is the best weapon to learn as it is universal and can be used to practice the movements of the sword, bayonet, and naginata, and even used as a substitute for a gun. Because jō includes so many elements of approved national education practices, such as physical exercise and games, it is a very useful means for developing physical strength, fighting strength, and spiritual strength.

At the Sea Scouts (ed. Japanese Boy Scouts), we have been using staffs for a decade in physical education, and they have proven effective as a substitute for manipulationg guns as well as in martial arts training for the boys. I have been teaching jōjutsu to youth groups for many years, and they have been very successful, widely recognized as a necessary style of national defense training during these times of national emergency.

The late Kanō Sensei said that you do jūdō not just for its own sake (ed. i.e., not for competition or rank, but as preparation for life and danger). When an enemy attacks with a weapon, use whatever you have to counter the attack, knock their weapon down, and then close to the enemy and attack. Catch, throw, push the attacker into submission. It is said that jōjutsu is the best method for suppressing such an attack, and its unique qualities were recognized (ed. implicitly meaning the qualities were recognized by Kanō Sensei) and the Kōdōkan adopted jōjutsu. In April of this year (ed. 1941), Nangō Jirō Kanchō (ed. Kanō’s relative and 2nd head of the Kōdōkan) asked that we include jōjutsu as a subject for advanced jūdō training, and it is taught to all those students. As a result, cane techniques are being used in jūdō to knock down an enemy’s weapon, opening them to a counterattack of great power (ed. he seems to imply to a jūdō counterattack–having neutralized an attacker’s weapon, drop your own weapon, grab the enemy and throw them down).

Last example of the qualities of jōjutsu. There was a certain painter who was almost 50 years old. When he was young he had done jūdō and had been quite strong, however, his body had deteriorated with age and he found even holding his calligraphy brush loaded with ink to be a challenge. His aged mother was worried about his health because of his lack of daily exercise, and he became anxious as well. He could not take up anything as vigorous as jūdō or kendō and was at a loss for what to do. Then he learned of jōjutsu and started coming to my dōjō every morning. After just 6 months, his body became vigorous, his heart strong, and he could even run again. When the Shanghai Incident occurred, he successfully joined the military to serve the nation. This is just one case where jōjutsu training allowed someone to restore their health and then take up their duties.

The Staff of Manchuria

Turning now to the remarkable developments in Manchukuo. In January, 1939 Anazawa Shidōin (ed. “shidōin” is an instructor) was sent to the Manchukuo Association Training Department for jōjutsu training. Then in May, Teru Kawachi was dispatched to train in the art of jōdō (ed. note, Shimizu Sensei used jōjutsu and then jōdō in the article). After visiting various provinces in Manchukuo to teach the course (ed. I believe he is referring to his own first trip to Manchukuo to teach jōdō that happened in 1939), there were increasing requests from various training centers for teaching the art, and it began to spread across the country. In January of 1940, Sawamura Masanori (澤村政則), Harada Tadao (原田忠夫), and Nakajima Asakichi (中鳥浅吉), as well as others, planned to go abroad and teach jōdō. As each instructor arrives in Manchukuo, seminars are held at various locations. Jōdō fever has grown and the art has become very popular, developing rapidly.

After receiving their training, jōdō trainees carry staffs and stand guard during peacetime. During the outbreak of a contagious disease, we cooperated with police to assist in managing traffic and acting as security guards. In Tonghua province, we fought bravely to help subjugate bandits. As our true worth has come to be recognized, the Youth Supervision Division in April of 1941 made jōdō a required subject at all youth training centers, and included it as a regular subject in national elementary and junior high schools. (ed. the Youth Supervision Division was an official government agency overseeing youth education in Manchukuo).

Jōdō instructors in Manchukuo are mainly jūdō or kendō people with dan ranks, but when it comes to teaching jōdō, they are all passionate in teaching each student that comes to them. And the students are equally enthusiastic, working hard to train in the art of jōdō, happily receiving the teachings. I sincerely hope that jōjutsu will be popularized here in Japan, along with jūdō, kendō, naginata, and other arts, and spread throughout the country as it has in our ally, Manchukuo.

Women and the Staff

In closing, I would like to say a few words about women and jōjutsu. Women who do naginata already have staff techniques contained within their naginata art. This is because if the blade of the naginata is cut off in a fight, the shaft must immediately be used as in jōjutsu.

Women usually carry umbrellas and these can be used to stab an enemy, defeating them with a single blow. A broom handle, bamboo pole, or whatever is at hand can be used to punish a thug. When I travel to foreign countries or visit dangerous areas with my family, I always carry a cane that I can use in an emergency. If you remain calm in a crisis, you can take appropriate actions to drive off an attacker. In short, if you train in naginatajutsu, you can simultaneously train in jōjutsu so that you can use techniques even without a blade.

As mentioned above, there is no limit to the techniques and applications of the staff. However, jōjutsu is an ancient Japanese martial art and most importantly, its guiding spirit must not be misunderstood. To emphasize the scope of its spirit, I would like to close with a story.

Peacemaking with the Staff

In Yuki, Shimōsa, there was a master of the Toda school called Fukusawa Kakyu, and a master of the Yoshioka school named Jurobei. The disciples of the two schools were endlessly arguing, telling each other about their respective master’s style and its superiority. Finally, the masters themselves began to feel pressure to meet and see who was the superior swordsman.

Kakyu was warm-hearted and reluctant, but Jurobei, a wealthy local, proud of his school, finally said, “Okay, I’ll definitely show everyone what I can do.” So one morning he went to Kakyu’s garden where Kakyu was tending his chickens. Jurobei had his Shintō Shimozaka katana three shaku long. He drew it and began warming up, insisting that they fight. Finally, realizing he had no choice, Kakyu drew out his kotō Bizen sword, a wakizashi 1 shaku 3 bu long, and quickly cleaned it. Kakyu didn’t even have time to change out of his muddy old farmers geta, he followed Jurōbei down to the riverbank.

A crowd gathered round when people realized the two were going to fight. Jurobei aggressively started the fight and the crowd gasped as his long Shintō sword chipped with every blow against Kakyu’s old Bizen sword. Despite his efforts, Jurobei could not get past Kakyu’s guard. However, Kakyu’s wakizashi blade was too short for him to easily get inside to cut Jurobei. Then, in the heat of the fight, Kakyu’s geta got stuck in a stone, the cord broke, and he fell to the ground. Jurobei immediately leapt forward to finish Kakyu.

Just then, a bystander in the crowd flew between the swordsmen; using his oak staff he stopped Jurobei’s cut in its full power. “Stop. Kakyu-dono has not even had time to clean his geta. It is unmanly to force a fight and then hit your opponent when they have fallen. In any case, your sword skills are inferior to Kakyu-dono’s. I am Magoemon of Fukawa, and I ask that you let me settle this match.” It is said that through his intercession, he convinced the two rivals to make peace. A sailor by trade, Magoemon was also a master of the Katori bō style. (ed. the founder of Shindō Musō ryū is said to have received menkyo in Katori Shintō ryū and his training may have included bō.)

~This is the end of Shimizu’s article~

Who was this article written for? Obviously, the market for the magazine is younger men/boys and perhaps girls too. Think an age range of 10 to 20. There is a lot in this article to appeal to that market with Shimizu’s discussions about how the art teaches universally useful lessons, how it enhances the quality of your life, and how his young students in Manchukuo have actually helped serve society using the staff. Then there is his brief, but direct, appeal to young women that jōjutsu is a great addition to their naginatajutsu with practical applications in daily life.

That said, it seems clear that there is another audience the article is designed to appeal to, and that is the world of top martial artists and government policy-makers. Shimizu emphasizes that equipment for jōdō is cheap, easily maintained, easily produced, stored, and distributed–all in implicit contrast to swords, or to kendō and naginatadō equipment. For a nation of limited resources mobilizing for multi-front war, this resource based appeal would be attractive. Shimizu also makes a strong case–and explicitly says–that jōdō should be taught in the nation’s school system because it is so effective as a martial art and a good way to teach basics that would apply with other weapons, even firearms. And throughout, he returns again and again to the spirit of jōdō, that it is the concentrated essence of BU / 武.

On balance, my sense of the article is that it is this second, adult audience that is more the target of Shimizu’s writing than young people. He wants official support for his jōdō, as he found in Manchukuo, and he is making the strongest case possible that this would be good for the country at a time of national emergency. This article could be seen as a “marketing” pitch to his seniors in the Dai Nippon Butokukai world, and to the political leadership trying to pragmatically discern how to spend money and scarce resources while making policy that would prepare the people for the hardships of war.

In any case, it is interesting to look back 80 years to how Shimizu was first introducing his art of jōdō to his peers and the country. It is interesting too how he lists the positive attributes of jōjutsu and sort of waves those qualities over to his new art of jōdō. Shimizu Sensei seems to largely erase the line between the koryū and gendai arts in this presentation, using the two words almost interchangeably. He borrows the lustre and depth of the koryū to add polish to his new art of jōdō, tying classical traditions to new thinking about the value and content of martial training.