My art, Shindō Musō ryū, is a koryū Japanese martial art. “Koryū” is a term used to indicate a martial school established before the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868.1 As a general matter, all koryū arts contained some material that was considered a secret–inner teachings reserved for a select few. This reliance on secrets to maintain the integrity of an art’s line, the core material that sets it apart from other arts, or one teacher from another, was a feature not just of budō, but of the geidō generally (arts and crafts and theater as well as martial arts) and religion.2 In this essay, I will touch on older secrets and then shine a spotlight on what amounts to a modern secret about Shindō Musō ryū.

Shindō Musō ryū’s secrets are classically material of the ryū that is supposed to be exclusively for members, with a particular emphasis on the centrality of material reserved only for menkyo or (for some material) menkyo kaiden. A menkyo is a master of the art and receiving the title of kaiden signifies they have all of the mysteries of Shindō Musō ryū. There is much that might be said about the role of menkyo kaiden in Shindō Musō ryū. Basically, the kaiden are the only ones with full authority to reproduce the art–to create new menkyo kaiden, keeping the art alive and thriving into the next generation.

The ryū depends on the quality of each kaiden’s embodiment of the art, their embrace of its deepest qualities, and capacity to teach to maintain the integrity of our art. Yet each kaiden is unique in their skills, strengths, interests, understandings, and how they manage their deshi (think “disciples”). We have traditions, but we also know that the art has constantly evolved, and still does evolve. There is no headmaster, and there are no menkyo police to enforce a single expression of the art. Each menkyo kaiden has seemingly complete authority to define the ryū and reproduce it as they see fit.

Because of the secrecy that permeates the art, and the vast spread of kaiden from (first) Fukuoka, to Tokyo, then throughout Japan and now around the world, knowing what another line of menkyo kaiden has or doesn’t have, practices or doesn’t practice, is not always easy to discern. We appear to agree on what sets of kata are considered “classical”, but we can’t agree on how to do those kata and perhaps not even on their central pedagogic purpose. Even two students of the same teacher do the same kata differently. Looking broadly across the ryū, there is no authoritative central clearing house of who has kaiden and no compilation of what material or secrets should be carried by all kaiden with the exception of the five gokui kata.

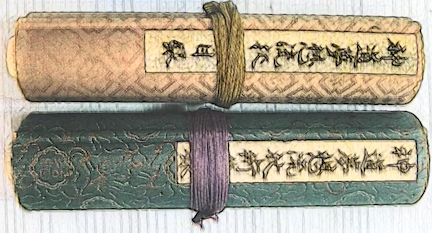

One thing we have in common across all lines is that a menkyo has been signified by receipt of a scroll of transmission from their teacher. The paper is essential to prove that you stand in the line of Shindō Musō ryū going back to the founder. My menkyo scroll is from Kaminoda Sensei. He signed it, marked it with his seals, and stamped it into his student book. His teacher was Shimizu Takaji Sensei, who got his menkyo kaiden from Shiraishi Hanjiro Sensei, and so on all the way back to Musō Gonnosuke. My kaiden is from Steve Bellamy Sensei of Nagoya, who got his kaiden from Kuroda Ichitaro Sensei, whose teacher was Shimizu, from Shiraishi, and so on all the way back to Musō Gonnosuke. Lineage is important and the menkyo scroll signifies where we stand in the line.

To have menkyo from Kaminoda and kaiden from Bellamy puts me squarely in the middle of the Tokyo branch of Shindō Musō ryū. It is on the basis of my work with Kaminoda Sensei, and then with Bellamy Sensei, that I can write anything meaningful at all about secrets in Shindō Musō ryū, but I would never claim to know everything, not even everything that they knew. I have what they wanted to give me, what time and language allowed them to share, and what they thought was important for me. Even though I have kaiden, I feel that there is much more to learn about the art, and I keep collecting information from reading and from talking to other members of the ryū. Most importantly, I keep reflecting on the ryū broadly, and the kata themselves as they contain a lot of information that is not obvious when you first learn them. This is the same thing my teachers did even after (or maybe, especially after) becoming menkyo kaiden themselves.

I have an acquaintance who is primarily a kendō renmei jodō guy who once asserted that there were no secrets in Shindō Musō ryū. A couple of his seniors in the ryū, after cleaning up our spit-takes of morning coffee, gently corrected that view. I think everyone moved on, but I don’t think anyone really tried to explain what the secrets are. Let me tell you, in Shindō Musō ryū we have plenty of secrets. We have so many secrets that you can classify them as old secrets and new secrets. Perhaps it is secrets all the way down?

While everyone wants me to tell them the meaning of the old secrets, this essay is going to highlight the secret that has come to mark the ryu in the last 150 years. This is a modern secret that blinds us to a fundamental shift in what constitutes the embodiment of Shindō Musō ryū in the modern world. The old secrets? That will have to wait for Secrets, Part 2.

New Secrets

In its first 250 years (from around 1610 to 1868) Shindō Musō ryū evolved a comprehensive curriculum designed to prepare a fighter to take a staff and defeat a swordsman. The ryū succeeded in making “warriors with a stick,” to use Bellamy Sensei’s evocative phrase. If it had failed, the art would have literally died out. The men who studied Shindō Musō ryū in Fukuoka at the end of the Edo jidai were among the most stubborn, resourceful, and tough of the early Meiji era. They survived, took care of each other, and played an outsized role (perhaps not always for the best) in shaping Japan’s modern path. I believe that the ryū itself played an important role in shaping their tenacious spirits.

After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, every koryū faced the challenge of surviving when the rationale for practicing their weapon arts had been erased by changes in how society organized to wage war and keep the peace. With the dissolution of the han (1871) and then the Hatōrei edict banning swords (1876–the same year former samurai were given non-convertible bonds in lieu of annual pensions), the social and economic context for practicing koryū fighting arts simply dropped away. Any koryū art that has survived to our own time had to undergo changes in what was practiced and emphasized to become “modern” in some way, and that could have started as early as the 1870s. Shindō Musō ryū has certainly seen profound changes. I propose that the earliest changes, which were obvious to the generation that was born by, say, 1850 and lived until 1920 or later, are almost invisible to us.

Those decades after the launch of the Meiji era were full of despair and reinvention. Former retainers scrambled to find cultural continuity and economic stability. The changes they endured meant that old material that had been at the heart of most ryū lost its relevance, and what survived is what could be kept alive in a radically changing world. So here is the new secret that has been kept from us: the central modern secret of Shindō Musō ryū is that it was designed to build a warrior with a stick by using training tools that went beyond kata to polish a member of the ryū as an actual fighter.

I can imagine most people’s reaction to this, “it still does create warriors with a stick!” “How can that be a secret when it is so obviously true?” Or the always useful, “rubbish!” Those responses reveal just how successful the two or three generations of Shindō Musō ryū masters that led our art between the 1870s and the 1940s were in changing our practices and cloaking our nature.

Let’s engage in a little mental exercise: I invite you to share a cup of tea with me during a break in training. Imagine we are sitting in a dōjō in old Fukuoka. It is a cold day in March of any year between 1660 and 1860. The ume plum tree is blooming outside the dōjō. The dōjō itself is heated only by our vigorous training. We are probably of the ashigaru class, low level warrior retainers–foot soldiers–of the Kuroda han. While already trained in sword, our careers depend on mastering jojutsu, juttejutsu, and hojojutsu. These arts are the necessary training for those who do civil control jobs (what we would classify as “policing” today). We specialize in weapons that allow us to disable, disarm, and capture swordsmen–trying not to kill them in the process. When you and I entered that old dōjō, first we removed our own long and short swords to place them in racks. Then, bowing, we took up bokken and jo for training in Shindō Musō ryū.3

What are we doing in that space together? Trained swordsmen. Guards and enforcers. The guys who get called out to confront mean drunks staggering down dark, narrow passageways with three foot razors shoved into their hakama. Do we simply keep polishing our kata when we know all too directly that kata are only obliquely like a fight? We need to stop a swordsman as fast as possible to save our lives and protect others. Can you imagine that the kata as we do them today were all we would have done to prepare to face a real sword with our lives on the line? Frankly, if that is all that happens in that dōjō, I would look at you over that steaming cup of tea and whisper, “we need to find a better dōjō; this one will get us killed.”

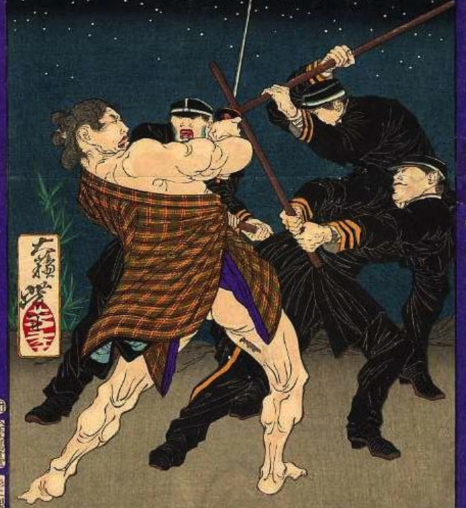

Setting aside (for a moment) the content of those exercises to polish a fighter, who dropped them and when? Many place the move away from old practices in Shindō Musō ryū on Shimizu Sensei’s shoulders. It is certainly true that Shimizu’s creation of “jodō” out of jojutsu in the 1930s marks a huge change in the way Shindō Musō ryū was being “costumed” for public consumption, but he was not alone in this effort as his senior in Fukuoka, Takayama Kiroku (he passed in 1938), was also working on this challenge. That effort at updating jojutsu led to Shimizu’s first book on jodō issued in 1940, with an eye towards spreading that art throughout Manchukuo and the Empire. The connection between (and the line that separated) jodō from Shindō Musō ryū became increasingly fogged in subsequent decades. (Photo below shows Shimizu Sensei with Manchurian students during a training session at Toyama Mitsuru’s Shibuya estate circa 1939.)

Shimizu’s changes impacted what is taught, practiced, and presented. However, that all happened in plain sight. In fact, Shimizu was staking his position in Japanese budō circles on his innovations. He was consciously changing the koryū art to better fit within the values and expectations of the gendai martial arts world shaped by Kanō Jigorō and Nakayama Hakudō and other influential kendō masters who were the “taste-makers” of the day. Jodō was on a path to fit comfortably with gendai versions of kendō, naginata-dō, and kyudō, and be appropriate to spread throughout the country, the Empire, and (in the post-war era) the world. None of that was secret. It happened in plain sight. But none of those innovations required that the deeper practices for members of the ryu had to change.4

And yet those deeper practices did change. My personal guess is that the changes to the daily practice of Shindō Musō ryū that led to the new secret I am pointing to started at least a generation before Shimizu. Shimizu may have added to the camouflage, but the effort to re-imagine training in Shindō Musō ryū probably predates Shimizu by 30 years. If I were betting when the choice to obscure the fighting core of kata crystalized, I would place it with the 1902-1903 seminar led by Yoshikawa Hanjirō (last head of the Jigyō dōjō) and Hirano Saburo (last leader of the Haruyoshi line). They took 3 senior students of the Jigyō line and 3 senior students of the Haruyoshi line–the two main dōjō of the late Edo jidai period–and taught them (at least) a consistent way of doing chudan, kage, and samidare. The joint seminar appears to have been motivated to save the art by creating enough kaiden to keep it going for another generation. The seminar was also apparently a vehicle for creating a coherent curriculum and waza to bind the lines together. Shiraishi’s subsequent choices around this material shaped Shimizu Sensei and Otofuji Sensei, leaders respectively of the Tokyo and Fukuoka branches of Shindō Musō ryū, and resonate down to us. Without this seminar, Shindō Musō ryū would probably have died out.

I suspect that year-long training also began to lay out principles for making Shindō Musō ryū relevant in a world without swordsman.5 One of those principles would certainly be that there was no need to regularly teach combative application lessons, which were potentially deadly and work best while practicing against a steel sword. Instead, the focus would become keeping the kata sets whole and intact because those carry the “DNA” of the art and can lead a dedicated practitioner back to many combative lessons. Shiraishi is the only one of those six joint Jigyō-Haruyoshi menkyo kaiden to pass the art to the next generation by creating (at least) three menkyo kaiden.

Letting go of routinely introducing practices designed to prepare fighters to actually fight was probably a conscious choice by the leaders of our ryū.6 The loss of the training designed to polish a warrior with a stick as a fighter means we are missing a huge piece of the original Shindō Musō ryū curriculum. Because none of us lived through any of those changes, and even the early students of Shimizu lacked comprehensive insight into the evolution of the art between 1876 and 1930, we simply cannot see clearly how the art had already changed before Shimizu stepped off the train in Tokyo to begin his distinguished career. The early students of Shimizu point to such things as the end of starting practice with kazari (a traditional ritual of reiho done to open a practice) as an example of innovations associated with Shimizu’s modernization.7 The valuable perspective of those early Shimizu students captures a snapshot in time of an art that had already gone through profound change, and it misses the end of other practices that would have been a regular feature of Edo jidai training in Shindō Musō ryū.

Do I have any evidence that something other than the kata as we know them occupied the training time and attention of jodōka and menkyo kaiden before 1930?

In fact, I do.

We have Shimizu Sensei’s own testimony. In an interview published in the Kengo Retsudenshu magazine (October, 1961 issue), Shimizu said that when he was young he was interested in Shindō Musō ryū so he went to Shiraishi Sensei’s dōjō to see the famous martial art of the Kuroda han for himself. What he witnessed was a single jojutsu-ka facing four or five swordsmen attacking at one time. Shimizu said that the feeling was so realistic that it took his breath away. He decided to begin training in that art as a supplement to judo. That was 1912, so we know that a randori-style exercise survived, at least among the most senior practitioners, late into the Meiji era.8

I have asked a couple of contemporary senior menkyo kaiden if they had any information about randori in jojutsu. The reaction of one was to sternly warn me to never do randori as it is too dangerous. I took that as a hearty “yes”. The other kaiden said his teacher had known of randori in Shindō Musō ryū, but that the “rules” for how to safely do it have been lost. Still, it makes sense that if you are going to be a fighter with a stick, you would have at least passing familiarity with how to face opponents coming at you in somewhat unpredictable ways and in numbers greater than one.

Are there other hidden tools for building a warrior with a stick that we know existed? Yes! The kata themselves preserve the “riai” or combative logic of how to use a staff in a given situation. Riai is a dense concept and I will use it in its most expansive interpretation in this discussion. The information contained in kata goes well beyond the somewhat basic “logic” that a sword should make a real cut to a real target, and that a jo player should not step into the range of a sword in a way that would get them cut. Beyond this, elements of “riai” would include teachings related to the setting and tactics of the exchange. In my experience, some of this information still survives and may be shared (somewhat haphazardly) in the course of training. If you listen closely to your sensei, you may pick up clues on how to “decode” elements of kata that begin to empower a practitioner to discover more on their own. For example, one kata may teach what to do when trapped in a corner while another lays out a method for funneling multiple attackers into a narrow channel to control their attacks. Almost every kata has a story to tell once you know how to look. Practicing out-of-doors helps with this decoding process, as some moves in kata appear optimized for certain natural situations. Comprehensive, routine treatment of these issues in training does not appear to be an element of most people’s kata practice as it surely would have been in the Edo jidai. Afterall, the “story” of a kata is a part of its training purpose. Much as sports teams work on particular plays for specific, anticipated situations, so it is–or should be–with kata.9

A different kind of teaching that has been obscured is what a real exchange between sword and staff is like. The kata are not to be mistaken for the actions of a fight. Kata are stylized to communicate particular lessons and polish particular skills, but they are not “fights”. Teaching a “fighting” version of kata–something that ends in one or two touches, has survived in at least two lines coming down from Shimizu (I cannot speak to what survived in Fukuoka’s line of Shindō Musō ryū because I have not had the privilege to study that style). These teachings amount to a “combative reset” or “saisettei”.10

To discuss just one of these lines, David Hall Sensei has said that Shimizu taught Donn Draeger combative-versions of kata. Draeger Sensei passed this material along to at least one of his students, who subsequently passed it to a few others that Draeger had authorized to learn the material. The practice that came down through Draeger amounts to abbreviated versions of the kata showing how a real fight would end, much faster than the kata we typically practice. These versions can be done against a steel sword (perhaps blunted), but also work with a bokken. Shimizu apparently learned these fighting “kata” in Shiraishi’s dōjō, but they were not commonly practiced, and the teaching of this material to Draeger was surrounded in secrecy. The saisettei is designed to let you come closer to experiencing the reality of fighting against a sword.

For jodōka preparing to actually face trained swordsmen, this combat-centered practice was probably more useful than the kata we maintain today. However, after swords were banned, the need to polish how to fight against a sword disappears (except–perhaps–for police who had to deal with criminals who continued to use blades). In fact, continuing to engage in this kind of realistic practice in a dōjō with dozens of students who have no real background in using blades, and in an era where sword’s are museum pieces not carry weapons, seems insane as well as unnecessary. It may have taken a generation for this inexperience with swords to represent the balance of trainees in a Fukuoka dōjō, but it would have certainly been the situation by the time of the 1902-1903 seminar.11

Both the “setting and tactics” lessons from kata and the core fighting lessons of kata are the kinds of material that strips away the chaff of a kata, highlighting the kernal within. Kaminoda Sensei always emphasized, as did his teacher, Shimizu Sensei, that the kata are precious. Kata carry lessons from real fights learned even at the cost of the life of a past member of our ryū. We must preserve the kata, but we should not preserve them simply for their own sake. Rather we preserve them because they carry the seeds of how to fight with a staff. What I am drawing attention to is that there was a time when revealing and polishing those seeds was an explicit part of our practice over and above learning the kata. That time is largely lost to us.

This secret regarding a combative reset is associated with another lost technique: using steel blades in training.

Remember that thought experiment of being in an old Fukuoka dōjō? We placed our blades in racks before practice. It is unimaginable in the pre-1876 world that you would practice, day after day and month after month, without sometimes experiencing the feeling of a staff against a real sword. It is very different to strike or sweep a steel blade compared to a bokken. Pre-Meiji era swordsmen would intuitively know that, and know that preparing to fight would mean some sessions against steel. Doing the kata of Shindō Musō ryū or Ikkaku ryu juttejutsu with a shinken–even blunted–changes the exchange physically and spiritually.

So using steel blades, explicitly teaching the complete riai of kata, learning the quickest way to win an exchange, and experiencing some version of randori are all tools that we can be confident were used in the first 250(+) years of Shindō Musō ryū. Effectively, all of that material has dropped away as common training practices during the last 120 years. In their place we have 12 kihon, 64 classic kata and 8 modern kata created by Shimizu. Most Shindō Musō ryū “students” spend all of their time polishing that curriculum, mostly on smooth dōjō floors, to a judging panel’s standard of excellence. Almost no one seems to stop and reflect that nothing about what they are doing could possibly resemble the working practice of a jojutsuka from 150 years ago.

The combatively attenuated versions of the kata that are practiced in modern jodō are as close as most people are ever willing to get to a real fight with weapons. Many find those kata exhilarating and, at least when they begin, a little frightening. Am I advocating for members of the ryū to step beyond modern practices and revive training with steel blades and randori? My short answer is “no.” But the matter is complicated.

Whoever decided to stop teaching more combative exercises in regular practices was right to drop them because competence with blades is hard to find and just learning the kata is a heavy lift for most people. Without mastery of the kata, and (particularly) without competence with blades, these suppressed practice tools would be profoundly unsafe. I cannot in good conscience recommend that anyone take up these kinds of tools and techniques until those involved have years and years of training under a proper instructor. Even with bokken, many of these practices could lead to serious injury or death in the hands of inexperienced practitioners. Do not try this at home!

However, I believe all practitioners should be aware that such teachings used to be central to our preparation. Also, there are some kinds of training that would prepare people for more combative explorations without having to go all in on live blades or unconstrained randori. Certainly for those who have dedicated themselves to training a decade or two should have exposure to some of this combative training to appreciate the depth of the ryū. Only then can you say you are keeping to the true path of the ryū.

The accomplishments of those who do ZenKenRen jodō are moving and impressive–the art is absolutely beautiful with its combination of speed, timing, and power–but the kata of ZNKR were never intended to inculcate the same depth of combative meaning as the kata of the ryū, which exist in relationship to elaborate sets that compliment and enhance each other. The efforts by contemporary members of Shindō Musō ryū to simply keep all our kata alive is amazing. There is so much material, including ancillary weapons, that it takes a decade or more just to learn it all while living a complex, modern life. But an old piece of advice–often attributed to Musashi–is that “you can only fight the way you practice.” No one in ZNKR jodo, and almost no one in Shindō Musō ryū, is practicing to fight. The kata by themselves were never used alone to build a warrior with a stick. Whether consciously hidden or unconsciously abandoned, most of our connections to practices meant to prepare a jodoka to be combat-ready have dropped away. That means that almost no one is living up to the art’s central purpose of building warriors. In a world without swordsmen this may be fine, but let’s not kid ourselves about what has been lost in our art.

The implications of that loss are a matter for another time.

Endnotes

1. The exact line that divides koryū arts from gendai, or modern arts, is not written in stone. One could argue that only arts rooted in actual battlefield applications qualify as koryū, so roughly 1600 would be the cutoff; this is not a common position. Many consider the end of the Tokugawa/establishment of the Meiji era as the turning point with 1868 as the common date used. Others believe that the koryū would include arts practiced and established prior to 1876 when the Meiji government issued the prohibition on carrying swords (the “hatorei”). Practically, I do not know how many arts could say they were founded between 1868 and 1876, setting us all to arguing about which label to use for the art. As for the translation “Koryū”, the literal (and poetic) reading of “old flow” is often used because it captures the feeling of how these arts are passed, generation to generation. Another quite common reading would simply be “old style” or “traditional”. Classical martial traditions is also perfectly fine. I tend to use the simple “old schools.” For another take on what makes the koryū, very close to mine, see Diane Skoss’s “What is Koryū Bujutsu,” https://shutokukan.org/a-koryū-primer/ . David Hall has a fine, and longer treatment on “koryū” in his excellent Encyclopedia of Japanese Martial Arts.

2. The topic of secrets in Japanese arts is worth more attention as it applies to Shindō Musō ryū. I highly recommend Berhnard Scheid and Mark Teeuwen, eds, The Culture of Secrecy in Japanese Religion, Routledge, New York, 2006).

3. Some think that ashigaru were only allowed a short sword, and this would be true in most feudal domains during the Edo jidai. However, some domainal lords allowed ashigaru to carry two swords and this was the rule in the Kuroda han. Excellent discussion of Kuroda han organization of retainers can be found in David Douglas Brown, From Tempo to Meiji: Fukuoka Han in Late Tokugawa Japan, Ph.D. dissertation, (University of Hawaii: 1981), p. 49.

4. The best piece in English on Shimizu Sensei’s reimagining of Shindō Musō ryū as modern jodo is Mark Tankosich’s “The Path to Zen Ken Ren Jodo; An Abbreviated History of Shindō Musō-ryū and the Advent of Its Modern Offshoot,” Classical Fighting Arts, v. 3, no. 55, 2017.

5. I am hoping that someone finds fuller documentation about this year-long training to shed light on all that was covered in that work.

6. It is impossible for me to prove this hypothesis without new research materials being uncovered. However, it does not matter whether the practices were lost through conscious choice or through inattention. Anyone who currently holds Menkyo and teaches knows that the time you have to teach anything beyond omote, chudan, ranai, and kage kata sets (and seitei) is extremely limited. When is there time to do the kinds of combative lessons I discuss in this essay? When is there a practice space for the most senior to safely explore these things consistently? Practical changes in how members of the ryū spend their time and earn a living places a limit on immersion in the ryu that did not exist to the same degree prior to Meiji.

7. Hamaji Koichi, Jo no Hinkaku (the dignity of the jo), English Translation published 2010. Discussion about changes in how jo was taught and practiced takes up several pages, but the focus on reiho can be found on page 14.

8. Kengo Retsudenshu (October, 1961) article, pp. 215. Note that his top Tokyo police SMR students were with him for the interview. Kuroda and Agatsuma participated in the interview, while Hiroi, Yoneno, and Kaminoda appear in the technical photos. Article (including an English translation) is available here: http://www.robertg.com/martialarts_articles.htm .

9. In baseball, teams practice “bunting” both as an offensive and defensive move. In soccer, teams practice specific arrangements for how to manage penalty kicks or corner kicks. In American football, teams practice “2 minute drills” for how to move a ball the length of a football field when time is running out in a game. These practices are intended for players to know what to do to manage a recurring type of situation. A jojutsuka could anticipate being in particular settings with predictable interactions with swordsmen–think of having to guard a gate or identify and apprehend a criminal in a narrow city lane–and lessons for these events are in the kata.

10. 再設定 is the likely kanji. I have only ever heard this said aloud; never saw it written down. Note that the jutte was trained alongside the jo but we have almost no evidence of how intimately these two weapons were tied together in the day-to-day lives of our predecessors. Certainly there would have been material around how, when, and why to transition from one weapon to another.

11. Image is by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (Taiso), 1875, Yubin Hochi Shinbun, No. 614b, “Tokyo Officers Nab Armed Robber.” Image is archived at William Weatherall’s Nishikie.com site, which serves as an excellent archive of many things, including Ukiyo-e published in some magazines and newspapers of the Meiji era.