“An umbrella can be used to stab an enemy, defeating them with a single blow. A broom handle, bamboo pole or whatever is at hand can be used to punish a thug. When I went to a foreign country or visited a dangerous area with my family, I always had a cane to use in an emergency.”

Shimizu Takaji, “Guide to Jodo,” Shin Budo magazine, December, 1941, p. 84 (translation by the author).

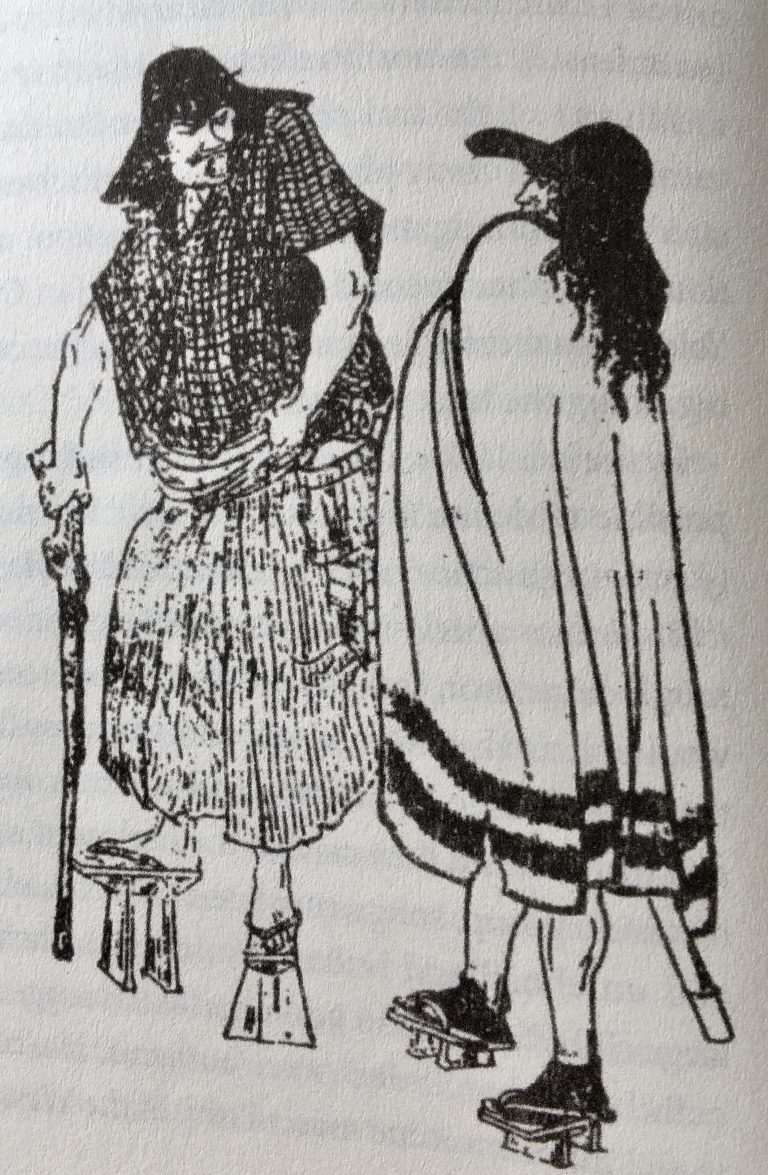

Shimizu Sensei, and his kohai, Otofuji Sensei, both learned the Uchida ryū tanjojutsu art (sutekkijutsu and tanjojutsu can be used interchangeably) and passed it to their students in Tokyo, Fukuoka, and beyond. Uchida Ryōgoro took combative lessons from jojutsu and juttejutsu and applied them to the cane. In fact, Shimizu and Otofuji reportedly learned the art directly from Uchida. Shimizu and Otofuji were masters of a koryū weapons art–Shindō Musō ryū jojutsu–but they were intimately familiar with Uchida’s creation which was very much a gendai art inspired by social changes during the Meiji era. (The image above is by Toshikata Mizuno, book frontispiece, @1900. Author’s collection.)

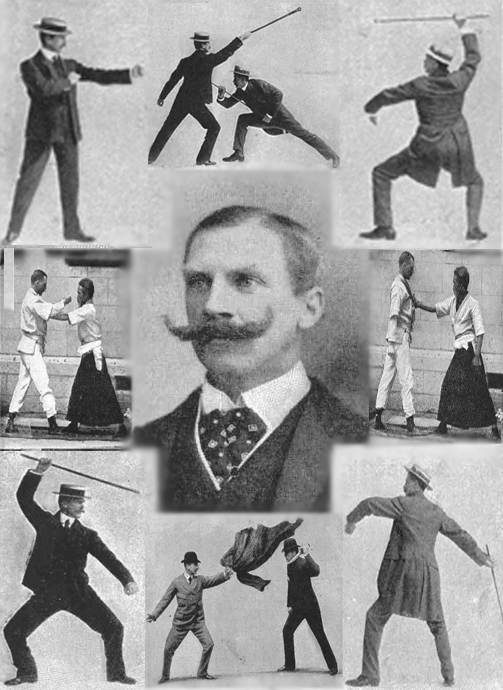

The story most commonly told about the creation of Uchida’s sutekkijutsu is that the growing popularity of western fashions, with men carrying western canes (and umbrellas) inspired this art. In this telling, the art was designed to provide the fashionable men of Meiji a way to defend themselves from ruffians and thieves. Basically, there is an assumption that sutekkijutsu was a Japanese analogue to the art of “Bartitsu”. Launched by Edward William Barton-Wright and first published in Pearson’s Magazine beginning in 1898, bartitsu’s target audience was very much the active gentlemen of London (and came into wider awareness due to Arthur Conan Doyle adapting it as Sherlock Holmes’ combative style; image below from Wikipedia entry on Bartitsu and credited to wiki editor the “artful dodger”.)

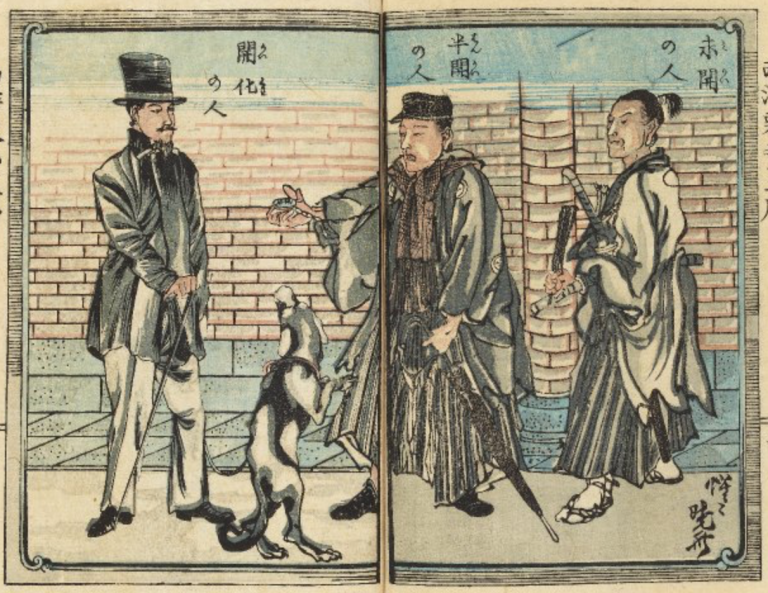

It is certainly true that western fashions, including men carrying canes and western-style umbrellas, came to be a key feature of Meiji culture. The image below is from an 1870 book by Kanagaki Robun, 西洋道中膝栗毛 (translated loosely as To the Western Sea on Foot). The print nicely summarizes how Tokyo urbanites of a certain class would see changing men’s fashions and the social significance of particular fashion choices. The man on the right is labeled “unenlightened”, the one in the middle “half-enlightened”, and the one on the left is “enlightened”–an accomplished gentlemen of the time. So just two years after the Meiji Restoration, and still six years before swords were banned, some social circles already frowned upon carrying a sword.

Source: British Museum Ukiyo-e collection. Art by Utagawa Hiroshige III.

However, to believe this “Uchida-makes-an-art-for-gentlemen” story, you have to think that the rough and ready warrior, Uchida Ryōgoro (who typically kitted out like the unenlightened figure above), created a martial art to help these guys…

Japanese artists in Paris, 1900 (wikipedia)

defend themselves from guys very much like these young men…

High School students 1929 “bankara” style.

I don’t buy this story at all. Instead, I propose that Uchida’s tanjojutsu was not designed to help artists fend off ruffians, gentlemen to suppress pick-pockets, or Lords to lord it over rabble-rousers. Uchida may have polished up some new kata or marketed his art to the gentlemen of Tokyo after he moved there around 1900. However, to believe this fashionable crowd was the original inspiration for the creation of his art requires ignoring who Uchida was, what circles he traveled in, and suppressing the fuller history of the emergence of short staffs as weapons during Meiji.

It is more probable that the origins of sutekkijutsu can be found among the rough former samurai, ashigaru, and lower level commoners adapting to sticks and umbrellas after swords were banned. Canes did become very popular in Meiji Japan, and, yes, some of this fashion change was certainly tied to the adoption of Western fashion, but what is missing when the discussion turns to the creation of tanjojutsu is that the ruffians were as likely to carry the canes as the gentlemen, and Uchida’s roots were closer to the thugs than the dandies. I will make three points in this article:

1. Uchida Ryōgoro was unusually prepared to create a gendai art based around the use of a cane.

2. Canes, sword canes, umbrellas, even roughly hewn branches (as shown in the first print at the beginning of this essay)–became the weapon of choice after swords were banned in 1876. One group in particular found short sticks to be highly useful in their “work”: the sōshi of the Meiji era. For these sōshi. a cane was not a fashion statement but an essential tool of their trade.

3. The Gen’yōsha, a Fukuoka-based political and social group that Uchida was a part of, ran their own gang of sōshi. The sōshi could be described as “political violence specialists,” and the Gen’yōsha’s tough lads would benefit from some training in short stick fighting. It is the Gen’yōsha organization, and its practical needs, that I believe inspired the beginnings of Uchida’s sutekkijutsu. That was far more likely to be the original market for tanjojutsu than the corpulent gentlemen or tender young scholars of Meiji sporting imported western fashions.

In short, Uchida Ryōgoro was the right rough man in the right dangerous place to provide polish to his organization’s need for cane-based violence. Uchida’s stick work would meet a specific and pressing need for “persuasive” violence that his organization could bring to bear on political life in Meiji Japan. Add it together and you get a more plausible story leading to the creation of sutekkijutsu than the normal “western fashion” gloss.

1. Uchida Ryōgoro’s Preparation to Create Sutekkijutsu

A lot is known about Uchida Ryōgoro’s martial education and experience. Information about Uchida Ryōgoro is pretty consistent and this is because modern writers (such as Matsui Kenji) rely on the same sources coming from Uchida’s son, Uchida Ryōhei, and from the records published by Gen’yōsha, the political organization Ryōgoro was associated with. Everyone should be aware that these sources are perhaps more hagiographic than biographic. Despite the unusually detailed information we have on Ryōgoro (compare what you know about Ryōgoro to his friend and neighbor, Hirano Saburou, to get a sense of how much more we have on Ryōgoro than his contemporaries), there are gaps and contradictions.

Uchida Ryōgoro was born into the Hiraoka family on April 9, 1837. His father, Hiraoka Nisaburō, was an ashigaru retainer of the Kuroda han with menkyo in the Jigyō line of Shindō Musō ryū. When Ryōgoro was about thirteen years old, he was adopted into the Uchida family, who were also ashigaru retainers of the Kuroda. The Uchida family lived next door to Hirano Kichizō, the famous jodoka who is best known as the head instructor of the Haruyoshi dojo. (Note that Hirano himself had been adopted from a merchant family.) Ryōgoro practiced Haruyoshi-style jojutsu and received his Shindō Musō ryū Menkyo kaiden from Hirano Kichizō in 1867.

Jojutsu was not the only art that Ryōgoro mastered. He also received menkyo in Ikkaku ryū torite (arresting arts) from Hirano Kichizo, as well as menkyo in Ono-ha Ittō ryū kenjutsu from Ikuoka Heitaro, Hōzōin spear from a certain Takeda, Kyūshin-ryū jūjutsu from Ishikawa Yubei. He also studied horsemanship, archery, gunnery and other arts. Note that Ikkaku ryū today is made up exclusively of the use of a jutte, tessen, and fundo tsuki jutte (hooked iron truncheon, iron fan, and truncheon with attached weighted short chain). Uchida’s menkyo scroll covers the full curriculum from the 19th century to include things like black powder pistols, weighted chain, simple truncheons, fold-out blades, rope tying and so forth. In short, Uchida mastered the full range of weapons that a man of his generation would be likely to need or encounter.

A notable quality of Uchida Ryōgoro’s preparation is that he studied calligraphy and classics under Hirano Kuniomi. Being a part of Kuniomi’s group also meant that he was exposed to “sonno joi” philosophy, which advocated for expelling foreigners and restoring the Emperor. Kuniomi was the second oldest son of Hirano Kichizō, and studied jojutsu under his father. However, he was a “Shishi,” the “men of high purpose” from the late-Edo jidai, and considered a famous Chikuzen patriot among the generation that worked to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate and restore the Emperor. He was said to be a friend of Satsuma’s Saigo Takamori.

In 1863, Kuniomi led a peasant uprising in Ikuno, Tajima province (modern Hyogo), but Imperial forces broke up the rebellion and captured the leaders. Hirano Kuniomi was taken to Rokkaku prison in Kyoto. In July, 1864 he was condemned to death, and was killed in his cell rather than taken to be beheaded. The story is that when the guards came to lead the condemned men to be punished, he demanded they kill him first and immediately. Kuniomi stood with his jacket torn open, chest bared and pushed against the bars. At his demand, one of the guards speared him through the heart while he recited his death poem. While the details sometimes vary around this event, the sum of the story is that he was anxious to offer his life in service of his Emperor and country. His early involvement with other Imperial restoration leaders made his name famous in Meiji-era Japan. If he had evaded capture in Ikuno, and survived the Boshin War, he probably would have been rewarded with a top position in the Imperial government as his rebellious peers were.

As a result of Kuniomi’s official condemnation, the Kuroda han ordered that his students be held under house arrest. This meant that for roughly 3 or 4 years, Uchida Ryōgoro and Hirano Saburō (both under house arrest) were living side-by-side with their teacher, Hirano Kichizō, able to oversee their polish as Shindō Musō ryū fighters. It seems likely that Ryōgoro and Saburō were able to practice together during that time as well. Hirano’s issuance of the Menkyo to Uchida came in the same year as the lifting of the order of House arrest.

A biography of Hirano Kuniomi was published in 1870 as part of a project of works profiling the Shishi of the restoration era. There was even a biwa musical piece created in his name, with lyrics that draw from some of Kuniomi’s writings. This tie to a nationally famous patriot would have given Uchida Ryōgoro some fame himself even if he had not been such a great martial artist. For a man from Fukuoka to have learned your bun and bu from Hirano Kuniomi and Hirano Kichizō respectively, would carry enormous catchet with a certain crowd throughout the country even decades after the Restoration.

Ryōgoro was released from home detention with the surrender of Shogunate forces. The Kuroda then, at long last, joined the Imperial side in the Boshin War, and Ryōgoro was dispatched (with other Kuroda army forces) to participate in the final battles. Ryōgoro is said to have distinguished himself as a fighter and leader. Returning from the war, he was promoted by the Kuroda and elevated to samurai rank from his ashigaru birth status. Social mobility of this kind across ranks was quite unusual and is a testament to the qualities Ryōgoro displayed in the Boshin war.

In the brief years between his return from war in 1869 and the termination of the Kuroda family as governors of Chikuzen, Ryōgoro worked on a military reform plan based on his experiences in the Boshin War. He was also put in charge of overseeing the clan armory at the castle. In 1871, when the Imperial government sent a new governor to take over from the Kuroda, he resigned his role overseeing the armory but appears to have remained in service to the government for a few years. When a widespread peasant protest broke out in 1873, Uchida organized a unit to respond. Using a kind of carrot and stick negotiation technique to build trust while also overawing the Hakata peasants in his area of operations, Ryōgoro succeeded in calming the rebels, and he advised other commanders to follow his model. He was ignored by some commanders, and other peasant groups actually broke into the city, burning and looting before being subdued. After this incident, he seems to have left the service of the provincial government.

Uchida Ryōgoro was respected among his peers for his tactical thinking. In 1877, some younger former retainers of the province came to him asking for advice on how to initiate a rebellion against the Imperial governor. The trigger for this effort appears to have been the uprising in Satsuma led by Saigo with the Fukuoka rebels wanting to interrupt Imperial forces then moving south toward Satsuma, using Fukuoka as a staging area. Based on his intimate knowledge of the castle, Uchida helped craft a plan to seize the castle, loot the armory, and then arm rebels to defeat government forces. In the end, the Fukuoka rebels were caught and the rebellion crushed. Uchida’s plan called for more forces to seize the castle and armory than the rebels could manage, and they failed to follow his outline for action. Uchida was himself declared a rebel and went into hiding for a few years. It is said that a local police official warned Uchida of his impending arrest and he escaped just ahead of the police unit sent to capture him.

When official attitudes had cooled enough for Uchida to return to Fukuoka, he is said to have entered the coal mining business. The stories around this are confusing. Accounts indicate that he and his brother, Hiraoka Kotaro (a menkyo in Shindō Musō ryū himself), got a mining concession which turned out to be largely worthless. This left Uchida impoverished, stuck in the mountains trying to make something of the mine, and relying on relatives to raise his family. However, at the very same time, Hiraoka Kotaro is said to have established a very successful mine business, become rich, and hired his brother to act as a manager for the firm (Shiraishi Sensei also worked as a guard for the company).

Putting all these events in a clear timeline is difficult with the sources we have, but the bottom line appears to be that Hiraoka ended up a very successful mine company owner, and his brother worked as a manager for the company. While there were undoubtedly difficult financial years in the late 1870s and into the 1880s, by around 1890 Uchida should have been financially stable. Hiraoka bankrolled the Gen’yōsha in the 1880s, and then established a home in Tokyo around 1890, being elected to the Diet in 1894. By 1900, Hiraoka Kotaro and Uchida Ryōhei were established in Tokyo, giving Ryōgoro a stable base from which to begin his teaching in Tokyo arriving there between 1900 and 1902.

Who did Uchida Ryōgoro teach during these years? We do not have clear reports regarding to whom or where Ryōgoro taught his arts. From the time he was made kaiden in 1867 until he moves to Tokyo around 1900, we do not have the names of any of his Shindō Musō ryū students save his own sons. Did he teach Shindō Musō ryū during those years? To whom and where? It isn’t until Ryōgoro relocates from Fukuoka to Tokyo (around 1900) that we have information on some of his other students.

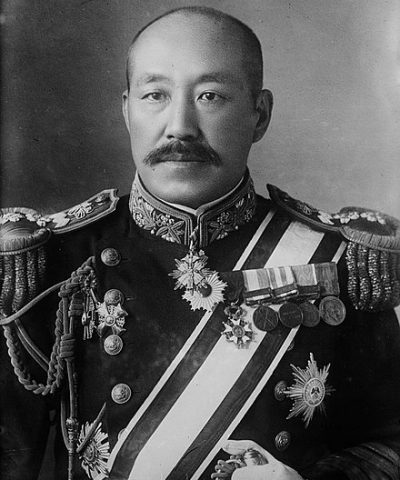

According to Matsui’s account, Uchida and his colleague, Takeuchi Kōhachi (1837-1908), demonstrated at the Naval Officers Club in 1902 and several influential students joined Uchida’s dojo. Naval officers Yashiro Rokurō (made a Baron in 1916 and full Admiral in 1918) and Shiraishi Yoshie (白石葭江), a hero in the Sino-Japanese war (he died in the Russo-Japanese war), began studying with Ryōgorō. Komita Takayoshi, the head of the Tokyo Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, also studied with Ryōgoro, and allowed him to use the Butokuden space in front of Shoen Park.

Another of Uchida’s students was the illustrious Nakayama Hakudō who began training with Uchida around 1900, practicing both Shindō Musō ryū jojutsu and shodo. These practices reportedly occurred at Komita’s dojo. Ryōgoro’s teaching of Shindō Musō ryū to Nakayama Hakudō lives on at Nakayama’s dojo in Tokyo, the Yushinkan. Nakayama’s style is so unique that it is hard to explain. Hamaji Koichi remembered as a child that Nakayama sometimes visited his home to train with his grandfather, Takeuchi Kōhachi, and attests that what Nakayama later did with jojutsu showed marked changes from what he was taught by Takeuchi. Hamaji Sensei’s theory was that Nakayama took lessons from his kendo practice and inserted them into his jo to serve his own martial purposes. According to Matsui’s article, Uchida Ryōgoro reportedly returned regularly to Fukuoka to teach at Shiraishi’s dojo and shared his sutekki-jutsu.. In this way, Shimizu and Otofuji Sensei would have both received sutekki-jutsu directly from Uchida Ryōgoro, who was senior to Shiraishi. (Ryōgoro was born in 1837 and received Menkyo Kaiden in 1867; Shiraishi was born in 1843 and probably did not receive Menkyo until at least 1902.)

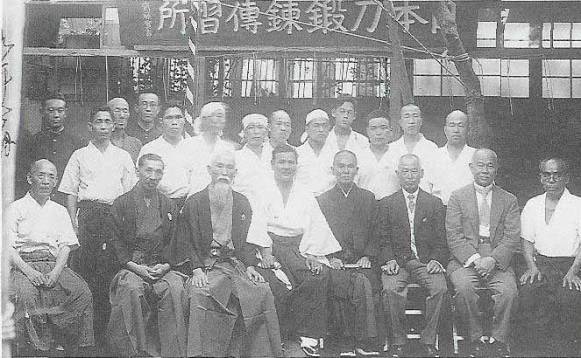

It appears that Nakayama Hakudō and Uchida Ryōhei both received Menkyo Kaiden in Shindō Musō ryū from Ryōgoro (there is controversy over whether Nakayama had sho moku roku, Menkyo or kaiden, but it is not for me to settle this and the Gen’yōsha history says Nakayama received all of Ryōgoro’s bojutsu). The photo below shows Uchida Ryōhei and Nakayama, probably in 1933, sitting together with the tosho (swordsmiths) of Kurihara Hikosaburo’s Nipponto Tanren Denshu Jo forge on his estate in Akasaka.

Nakayama Hakudō is sitting second from right, with Uchida Ryōhei next to him. Original internet source not available, but a different capture is still available at https://xingyusword.com/blogs/about-japanese-swords/history-japanese-sword

Uchida Ryōgoro was superbly prepared to create an art like tanjojutsu, which carries lessons from both Ikkaku ryū juttejutsu and Shindō Musō ryū jojutsu. The known Tokyo students of Uchida were distinguished naval officers and martial artists who travelled in elite circles. There is no evidence in the extant literature that I can find that Uchida was also marketing his sutekkijutsu to others in Tokyo. While the taste-makers of Tokyo may have studied with Ryōgoro at some point, I believe there was another market for this teaching that has gone uncommented upon in histories of sutekkijutsu: the sōshi–the political violence specialists who emerged with the beginnings of Japan’s parliamentary politics.

2. Violence in an Emerging Democracy and the role of Sōshi

There were six significant rebellions led by shizoku (former samurai) in the 1870s. The culminating battles were fought in 1877 in the Southwestern War, which saw Saigo Takamori’s Kagoshima warriors defeated by the new national army of the Meiji state. Organized violence on a large scale proved an ineffective means of resisting the social turmoil and economic dislocation of the Meiji government’s reforms. In the years after the defeat of Saigo, the shizoku were at a loss about how to effectively express frustration with the new Meiji government’s policies.

Many of these men had themselves once been the violent arm of the Tokugawa era “state”, but they found their use of legally sanctioned violence–and the swords used to deliver it– ripped away. Perhaps more importantlly, they found their economic standing completely erased due to the end of government pay and the issuance of government bonds that had limited value. Social turmoil was not limited to the shizoku, but hit all classes in some way. Farmers in particular were hit hard by efforts to deflate food prices and tax their new “land” and production. Many men, of all groups, were looking for new opportunities in a world that worked in radically new ways from the world they had grown up in.

After Saigo’s death and the collapse of organized violent resistence to Meiji policy, resistence to the new central government took new forms. Local political organizations began to emerge, and a cross-prefecture movement, the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement, came to prominance. Instead of organized violence designed to overthrow the state, these movements engaged in a spectrum of activities from speech-making to raise public engagement, political advocacy for a new Constitutional order, strikes and riots, and even targeted assassinations of Meiji political figures associated with particularly hated policy decisions. Unrest and dissatisfaction with the pace of Meiji reforms drove popular political movements; dissatisfaction with representation, and specific policy initiatives provoked new forms of violence.

From this turmoil, which marked the 1880s, a new class of actor emerged: the sōshi. The history of this label, which is often translated as “brave knight”–who coined the phrase and when it came to be widely accepted–is in dispute, but over the course of the 1880s it seems to have been widely adopted across the country to describe a kind of activist willing to use some form of violence to further the cause for which they stood (and, by the 1890s, sometimes the party that paid them for their services). The name carries an echo of the “Shishi” or “men of high purpose” who drove the overthrow of the Tokugawa and reestablishment of the Emperor.

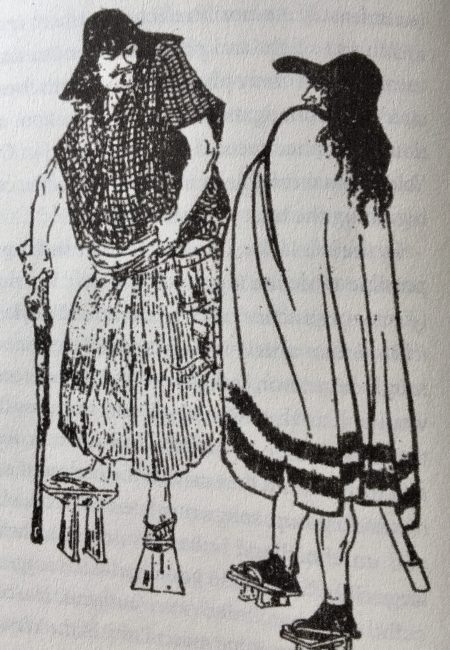

Sōshi engaged in various activities. A group might be found storming political meetings to disrupt organizational discussions or speeches, others might assault or try to assassinate government officials, and still others may have attempted to influence local elections through intimidation or violence. Sōshi were typically associated with political movements (or “bosses”) in various locale around the country. Their weapon of choice was a cudgel or cane–particularly a sword cane. Look carefully at the image above paying attention to the cane held by the sōshi with his back to the viewer. You can see a straight line cut just below his right hand, indicating that this is a sword cane and that line demarcates where the handle separates from the “saya” hiding the blade.

Note that this style of cudgel/cane is not what Meiji-era gentlemen generally carried, which were largely indistinguishable from fashionable European or American canes (although some of these staffs would also conceal a blade). The type of sword cane shown by Toshikata, and associated with the sōshi, is so rough hewn and generally thick that they are particularly distinctive. Below is an image of a sword cane of this type that came up for auction in recent years. This shikomizue ( 仕込み杖) shows the same kind of clear “cut” line where handle meets saya. (The image was captured from Yahoo.jp.)

An indispensible source for the discussion of this era is Eiko Maruko Siniawer’s Ruffians, Yakuza, Nationalists: the Violent Politics of Modern Japan, 1860-1960 published by Cornell University Press in 2008. Siniawer goes into much more detail about the political movements and the social pressures of the Meiji years, so if my poor summary intrigues you–go read the book for yourself. It is just a terrific work. and while it is not focused on martial arts, it does add a lens through which to evaluate and think about the survival of our arts into the 20th century.

https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801456824/ruffians-yakuza-nationalists is a link to Siniawer’s volume if you want to order it for yourself. I get no commission on this at all, but I think many who would enjoy this essay would find Professor Siniawer’s book a good read. While all sōshi seem to have embraced a willingness to use force to further their aims, they also sported fashion that was distinctive, and a kind of abnegation of Western fashion. According to Siniawer, the Shinano sōshi were known as “Buranketto sōshi” for the blankets that draped their bodies in cold weather. Other groups wore distinctive hakama or hats. Almost all seem to have worn geta, sometimes with very high “teeth” so that they towered over others. The topic of sōshi, and their role in Japan’s emerging political culture, was commonly tackled in popular magazines and newspapers. The image below is from Mainichi Shimbun from May 28, 1889 and shows a Kanazawa sōshi on the left and a Shinano “buranketto” sōshi on the right.

Image from Siniawer, originally Mainishi Shimbun 1889

As mentioned, sōshi were known for carrying canes or very thick rough sticks, sword canes, clubs (and sometimes pistols). Their weaponry, particularly their sturdy canes, was a distinctive affectation that immediately conveyed implicit violence. Of course the other issue with their sticks was that it was possible to conceal a blade inside the staff and it was not obvious whether you were looking at a cudgel or a blade (or both, think of how we use a tessen and jutte together in Ikkaku ryū) as a threat.

With the launch of a national parliament in 1890, the sōshi’s activities came to concentrate on elections and parliamentary activity. In the elections of the 1890s, there was finally a limited suffrage allowing those who met stringent property or tax levels to cast votes for parliamentary representatives. With such a small pool of potential voters, sōshi were used to try to target and intimidate voters into voting for the candidates that particular group of sōshi backed. At times, they also broke up large political meetings, charging into the group to attack people with their sticks, seizing the dais.

Sōshi could be described as a feature, not a bug, of the Meiji parliamentary politics landscape. Thousands would be mobilized during elections and at least hundreds swarmed Tokyo when Parliament was in session. The government and police were unable to wipe out the sōshi, and it is likely that the desire to do so was somewhat ambivalent as all political sides could find benefit in using violence as an arrow in their quiver to gain political advantage. Siniawer provides a long account of sōshi involvement in parliamentary politics starting with the seating of the first parliament in 1890. Sōshi were used by both the “ritō” (government) and “mintō” (people’s democracy) parties and politicians. Physical force became another arena in which parties and politicians could compete for influence.

Party assemblies in Tokyo were particularly rich targets for sōshi violence as party leadership would be gathered in one location. In a 1890 meeting of the Jiyūtō party, opposing sōshi invaded the meeting, disrupting the proceeding. One Jiyoto Diet member was surrounded by these sōshi, and “seven or eight sōshi beat him with sticks until he collapsed,” with serious head injuries. Other Jiyūtō party members grabbed chairs to beat back the sōshi, driving them into the lobby of the building. There rickshaw drivers and others joined the Diet members in beating the sōshi.

At other times, sōshi would try to catch a Diet member in isolation to intimidate or attack them. The Budget Committee Chairman of the Diet was said to maintain almost 100 sōshi to guard both himself and his home. Siniawer cites an incident at the Diet building in 1891 where a member was “hit on the right side of his face with an iron stick.” She then quotes Ozaki Yukio on the number of attacks on politicians:

“It was not unusual to see members arriving at the Diet all bandaged up. Inukai was wounded in the head. Shimada Saburō was attacked a couple of times and badly hurt. Takada Sanae was cut down with a sword from behind and the blade almost reached his lungs; he would have died on the spot had he not been obese. Kawashima Atsushi, Ueki Emori, and Inoue Kakugorō (ed note: the member hit with the iron staff mentioned above) were all attacked at different times and came wearing bandages. Suematsu Kenchō was hit by horse manure thrown from the gallery. Members often even got into fist fights on the floor of the House, which became a rather rough place to be.” (Siniawer, p. 63)

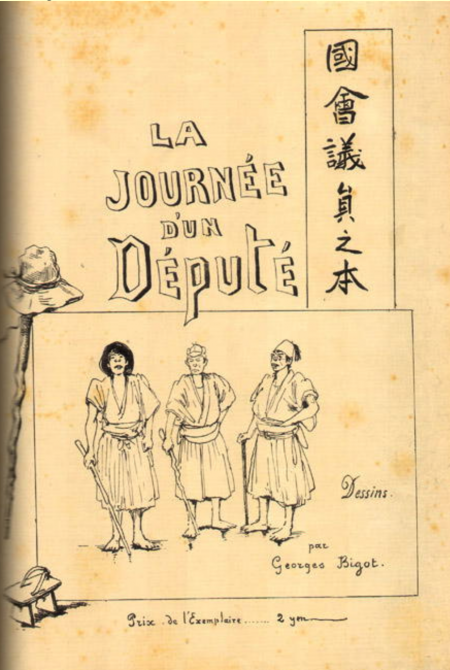

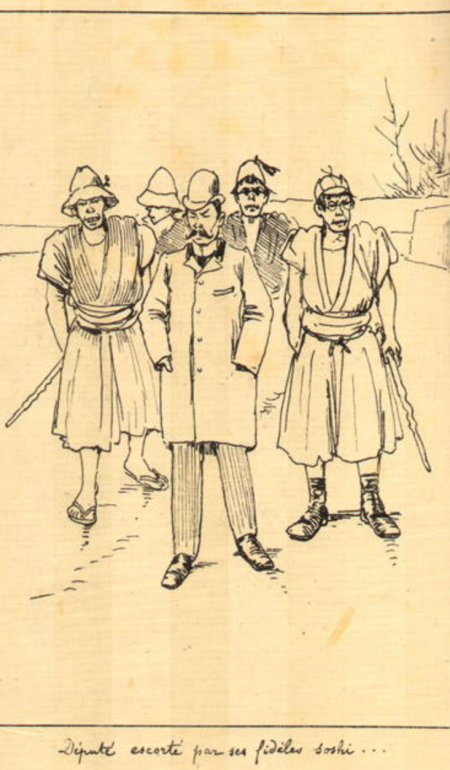

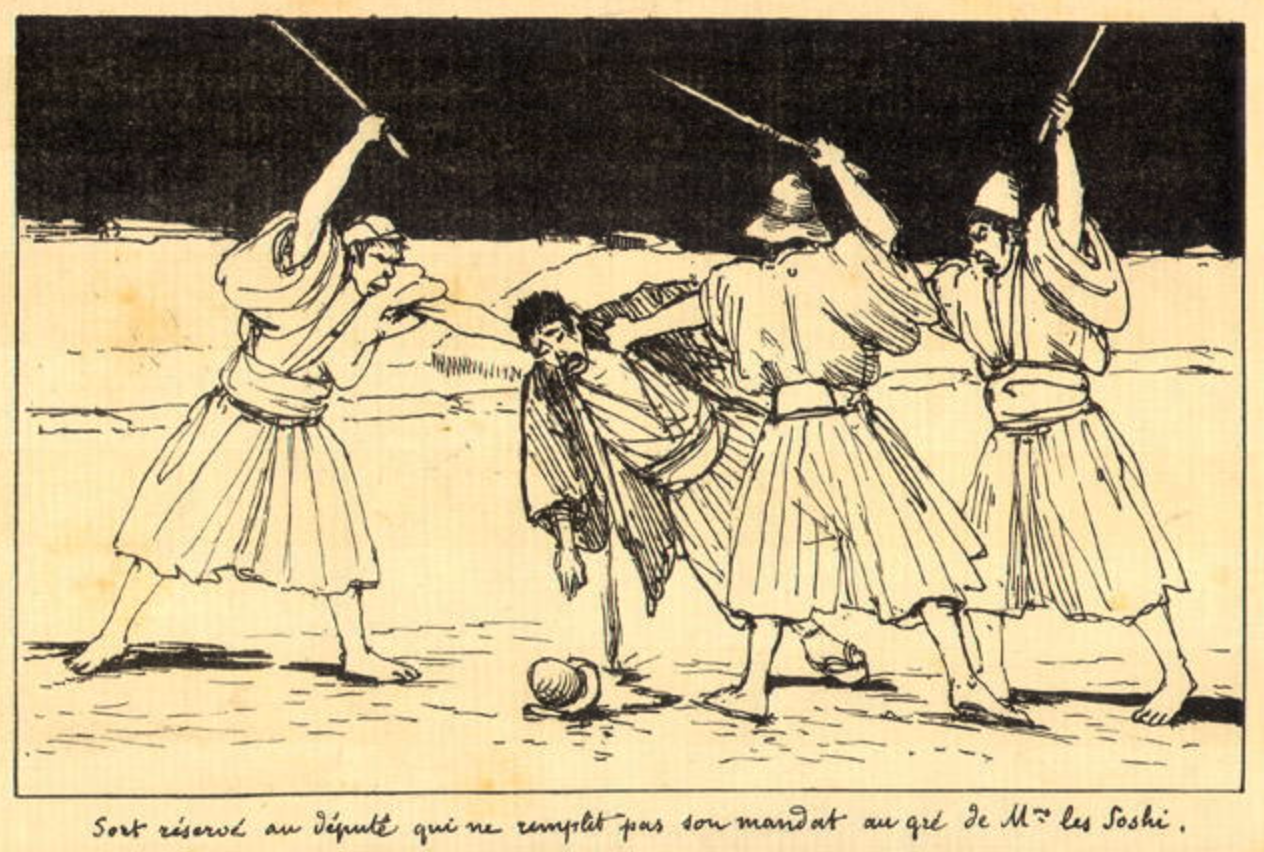

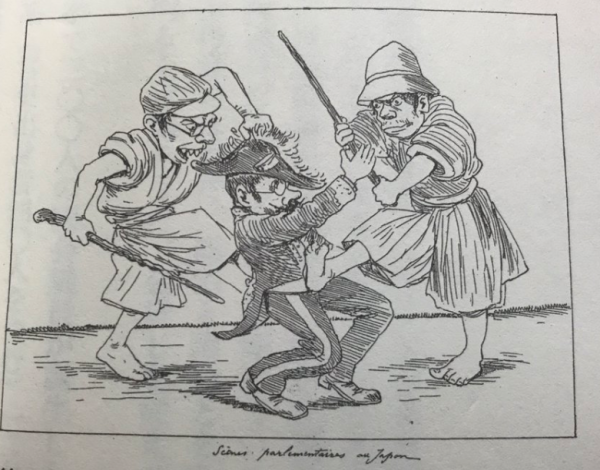

The images below are by the French artist (and resident of Japan from 1882 to 1899), Georges Bigot, from his small volume, La Journée d’un Député. The sōshi loom so large in the new parliamentarians’ day that the very cover is built around images of sōshi (and note the rugged cane at the left of the framing).

I do not know whether Bigot witnessed some or all of the kind of events represented in his images, but he was known for efforts to capture everyday life in contemporary Japan during his years there. This volume is thought to have been published after 1890 (there is no date published in the booklet). Two other images from the volume reproduced below make plain the way sōshi were perceived in their relationship to parliamentarians. In the first, we see a parliamentarian surrounded by his loyal sōshi. In the second, we see a parliamentarian under assault by sōshi. All three of these images come from Baxley Stamps, which carries excellent antiquarian volumes, and once had a copy of this book for sale. They generously reproduce all of the volume’s relevent pages at: (http://www.baxleystamps.com/litho/meiji/bigot_depute.shtml ). Bigot’s volume contains many more sōshi-related images if you are interested.

Another cartoon by Bigot, made in 1898, perhaps made after he had returned to France, shows a parliamentarian being attacked by sōshi. It communicates the violence of the sōshi, as perceived by Bigot, and the inability of supposedly powerful parliamentarians, here costumed as a state official, to control that violence. The title is “parliamentaires au japon” or Parliamentarians in Japan–with the portrayal leaving it ambiguous as to who makes the law in this situation where street violence seems to overawe legal office. I have not been able to identify where this image originated in Bigot’s work, but captured this from a social media source at https://x.com/fan_of_manga/status/933501739243782144 .

Motivations for individuals acting as sōshi appear fluid. Some were aligned with the politics of the group they were with, but others were simply paid thugs. Siniawer (p. 58) provides a quote (and translation) from one sōshi which has the tone of someone who is a stick for hire (reported in the Japan Weekly Mail, May 28, 1892):

“If I have some coadjutors, I can intimidate either farmers or merchants, or secretly assault a political opponent…. My stick is somewhat thick and clumsy but I have not money to buy a sword cane. I am accustomed, however, to carry [sic] this stick.

3. Uchida Ryōgoro and the Gen’yōsha

Where does Uchida Ryōgoro fit with the sōshi? Good question! He was a member of the Gen’yōsha, the political and social action group founded in Fukuoka around 1881. Among their wide-ranging activities in the Meiji era, the Gen’yōsha created and managed a gang of sōshi themselves. Some of those they mobilized may have been for temporary jobs around influencing elections, but they had a permanent or semi-permanent presence in Tokyo itself and were considered among the most effective and feared groups, amounting to a small private army.

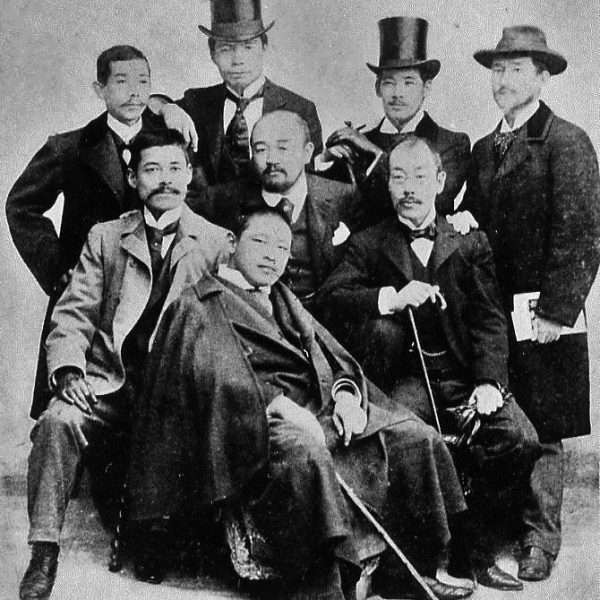

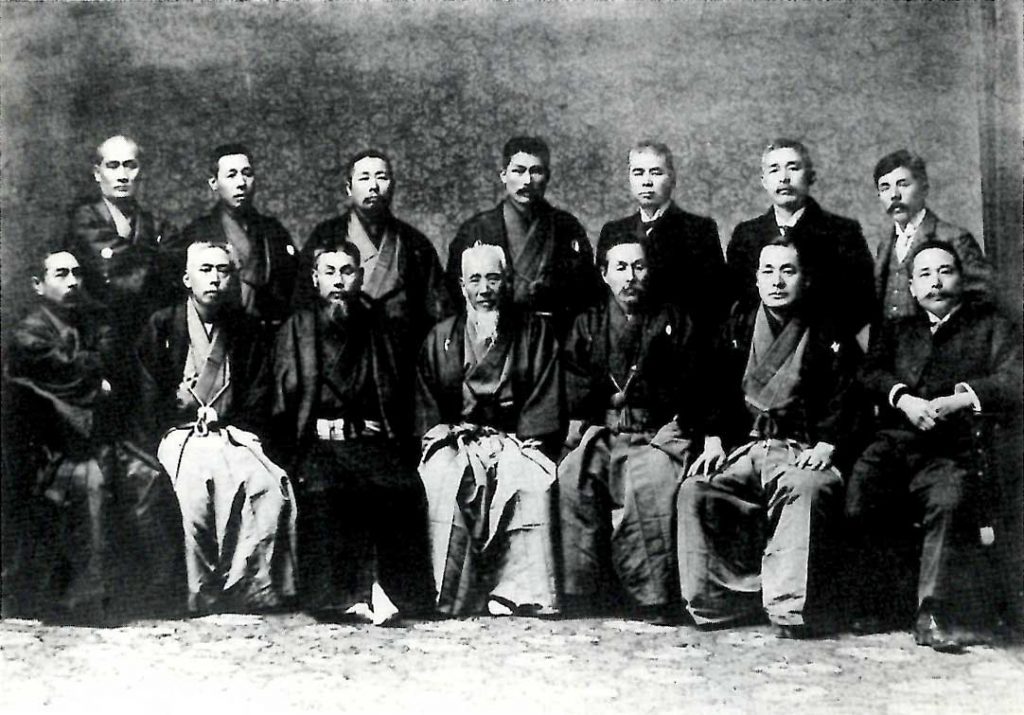

Portrait of the Gen’yōsha, captured at https://genyosha.jp/about/

The creator of tanjojutsu, Uchida Ryōgoro, sits in the center of this portrait taken of founding and important members of the Gen’yōsha (circa 1901). The image shows in the front row (left to right), Suenaga Jūnichiro (whose younger brother, Misao, plays a critical role in supporting Shimizu Sensei when he comes to Tokyo in 1930), Sugiyama Shigemaru, Tōyama Mitsuru, then Uchida Ryōgoro, Shindo Kiheita, Fukumoto Nichinan, and Hiraoka Kotaro. In the back row (left to right) are Kodama Otomatsu, Tukinari Isamu, Matono Hansuke, Uchida Ryōhei, Ōhara Yoshitaka, Koba Sobei, Takei Shinosuke. There is no doubt that Uchida Ryōgoro was a significant figure who moved easily among the leaders of the group, even if he was not one of the intellectual and political leaders himself. Though a generation older than the others, he had proven himself as a leader, tactician, and experienced fighter so it is likely that he was consulted on strategy and tactics rather than engaging in day-to-day political activity.

In the early 1880s when the Gen’yosha emerged (there were predecessor groups from the early 1870s), they established a school and a dojo. At that dojo, the Meidōkan, various martial arts were taught to young men including Jigo Tenshin ryū jujutsu, swordsmanship, and staff arts. Training the body in traditional martial arts was considered an essential quality of developing modern citizens who would be prepared to serve their country. (This discussion of motives draws from the fascinating 2015 doctoral dissertation by Moshe Lakser, “Politics, Work, Identity: Educational Theories and Practices in Meiji Era Fukuoka, 1879-1918.”) Whether some version of tanjojutsu was taught at the Meidōkan in the 1880s or 1890s is unclear. It is known that Uchida Ryōgoro had his sons study jujutsu there and probably had them study some kenjutsu as well.

During this same period, from approximately 1890 through the last years of the Meiji era, the Gen’yōsha maintained a substantial sōshi group in Tokyo and the Fukuoka region as well. The Gen’yōsha mobilized their supporters (at least) in the 1890 and 1892 elections. Political violence in the 1892 Diet election was widespread, with police aligning with pro-Government activists to suppress the vote for the people’s rights-oriented Mintō party. Hiraoka and Tōyama negotiated with the government to support Ritō candidates at the polls, suppressing Mintō candidates in the Fukuoka region. Tōyama Mitsuru, the political leader of the Gen’yōsha, later wrote of the election that “it was like a rainfall of blood in almost all parts of the country.” (Sang Ii Han, “Uchida Ryōhei and Japanese Continental Expansion, 1874-1916, Claremont Graduate School, Ph.D., 1974, p, 59.

According to Sang Han:

“Hiraoka and Tōyama led Genyōsha men and three hundred sōshi (political bully) from Sasa Tomofusa’s Kokkentō in Kumamoto to destroy popular support for Okada Koka. Shindo Kiheitai led another group, reinforced with ex-samurai from Akizuki, to the Asakura areas in order to destroy support for Tada Sakubee. Uchida Ryōhei, following Hiraoka’s orders, led several dozen mine workers to the area of the Kaho District, where he successfully and violently helped insure victory for government supported candidates at the polls.” (Han, pp. 59-60)

The Gen’yōsha, with hundreds of cane-wielding sōshi working for them over more than a decade, would have provided a need for an art like Uchida’s. Miners would have been a natural pool for finding and training men to function as sōshi, particularly for occassional election-related “field work.” Conveniently, Uchida was a manager at his brother’s mine company, and spent years in intimate contact with these rough laborers. My theory of tanjojutsu lays its origins squarely in this arena of political violence and personal development that were part and parcel of the Gen’yosha and its members.

4. Conclusion

I cannot prove that sōshi generally, or the Gen’yōsha sōshi in particular, were the driving force for Uchida to create his tanjojutsu. There is also no proof that the fashion-forward gentlemen of Japan were the original target market for his art. The one thing we can be sure of is that Uchida did not create sutekkijutsu kata for himself. His years of mastery of sword, staff, and torite would have allowed him to pick up a cane and naturally let techniques flow. Organized kata would only be for others with less training and talent.

Uchida’s group, the Gen’yōsha, were in the heart of political violence in the Kyushu and Tokyo areas, and their agents could use the kind of pragmatic fighting skills with short staffs and short blades that Uchida Ryōgoro’s sutekkijutsu taught. I believe it is far more likely that his art began in that rough crowd than in meeting the personal security needs of the dandies of Tokyo. If Uchida later marketed his art to those well-washed gentlemen their demand for those skills would probably have been driven–in no small measure–by the same cane fighting skills having already been passed to sōshi who roamed the streets of Tokyo and the halls of Parliament.

When we tell ourselves the story of where Uchida’s sutekkijutsu came from I think we should acknowledge the sōshi and their political violence as a probable origin. Writing the violent and unfashionable sōshi out of history, replacing them with the more palatable image of be-suited dandies, obscures our art’s probable origins.

Bibliography

Japanese Sources

Shimizu Takaji, “Guide to Jodo,” Shin Budo, December, 1941.

“The Legend of Uchida Ryōgoro,” Seinin Kiden, volume 2, published by Black Dragon Society, 1911. http://www5e.biglobe.ne.jp/~isitaki/page048.html

“Uchida Ryōgoro,” History of the Gen’yōsha, published by the Gen’yōsha, 1917. http://www5e.biglobe.ne.jp/~isitaki/page048.html

Shigeaki Gamo, Hirano Kuniomi Den, 1870.

Matsui Kenji . 1993. “The History of Shindō Musō Ryū Jojutsu,” translated by Hunter Armstrong and edited by David Hall (Kamuela, HI: International Hoplological Society).

Hamaji Koichi, Shinto Muso ryū: Jo no Hinkaku, an interview of Hamaji Koichi by Geoffrey Toff compiled by Hamaji Mitsuo, 2008. Translated by Hiroshi Matsuoka and Russ Ebert.

English language sources

“Hirano Kuniomi”, Chikuzen Biwa musical composition. https://guignardbiwa.com/en/library/hiranokuniomi/

Jeffrey Karinja, “A Lineage all but Forgotten: The Yushinkan (Nakayama Hakudō),” http://kenshi247.net/blog/2011/02/14/a-lineage-all-but-forgotten-the-yushinkan-nakayama-Hakudō/

Siniawar, Eiko Maruko, Ruffians, Yakuza, Nationalists: the Violent Politics of Modern Japan, 1860-1960, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Dissertations

Sabey, John Wayne, “The Gen’yōsha, the Kokuryūkai, and Japanese Expansion,” University of Michigan, Ph.D. dissertation, 1972.

Han, Sang Ii, “Uchida Ryōhei and Japanese Continental Expansion, 1874-1916, Claremont Graduate School, Ph.D. dissertation, 1974

Lakser, Moshe Nathaniel, “Politics, Work, Identity: Educational Theories and Practices in Meiji Era Fukuoka, 1879-1918,” UCLA, Ph.D. dissertation, 2015.